Vian Hussein: On Painting War Displacement & Belonging

Interviewed by Dr. Hawzhin Azeez

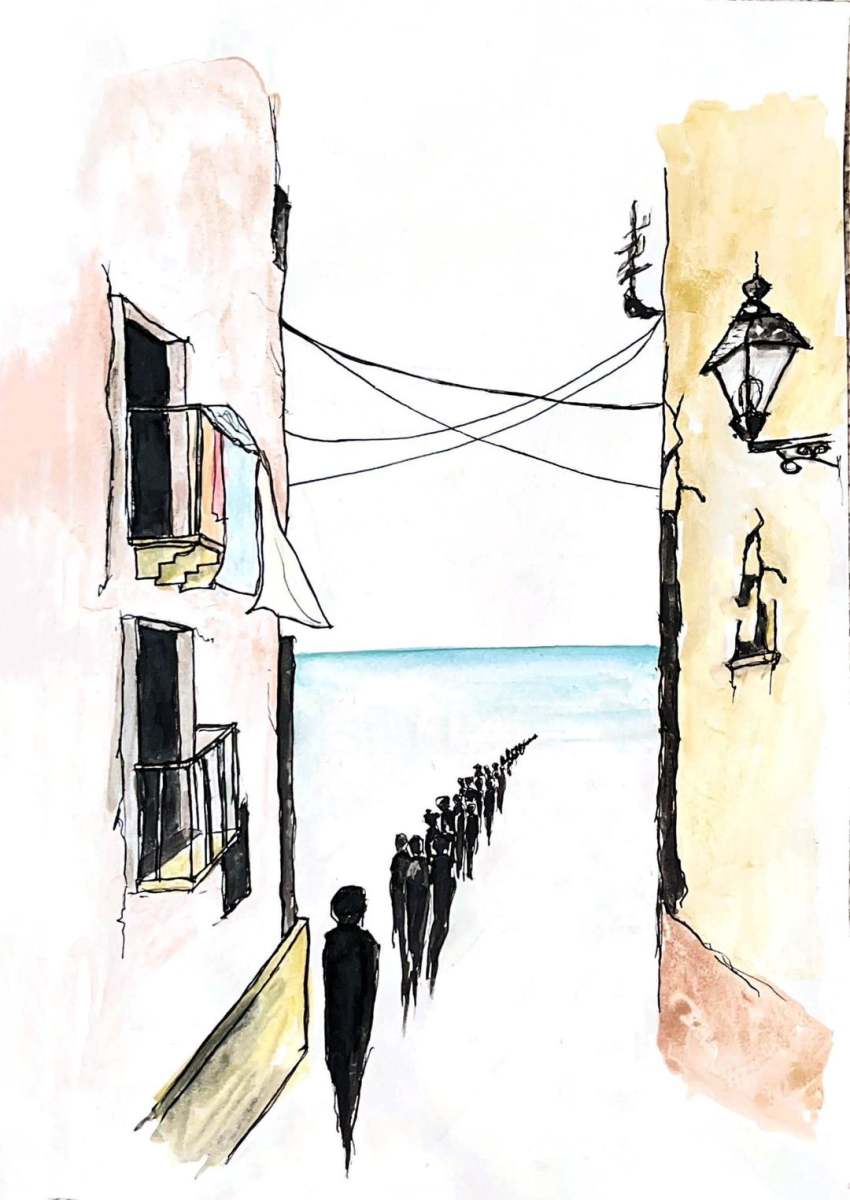

Vian Hussein is a rising Kurdish artist from Rojava, living in the UK. Her powerfully emotive pieces breach the boundaries between art and activism and moves us boldly across the emotional terrain of identity, gender, and belonging. Vian is a child of the Syrian Civil War, the offspring of displacement and asylum, of long treacherous journeys across the inhospitable oceans in search of safety and naturally her art is a reflection of her lived reality. For Vian, art can be a powerful avenue to challenge the deeply settled sense of apathy towards the plight of asylum seekers and refugees. Through her paintings we see how art humanizes, amplifies, challenges, and confronts the observer to view an issue or a subject from a different angle and a new perspective. With her art, Vian aims to break down gendered norms and social barriers around the utility of art and artistic expression in the developing world and even in the most war-shattered settings; indeed for Vian it is precisely at this point and time that art becomes revolutionary and its most powerful. And, perhaps most crucially, she aims to represent Kurdistan, and the Kurdish struggle for freedom and hope amongst suffering and pain, in a new light to a new audience.

Tell us a bit about yourself, your childhood and life.

My name is Vian K. Hussein, I’m a Kurdish artist from northern Syria (Rojava). I was born in 1999 in Aleppo city where I spent most of my childhood before my journey to seek asylum outside of Syria. As any Syrian-Kurdish child, I couldn’t complete my education because of the start of the Syrian Civil War, after my school was bombed. The interruption from education was one of the most difficult stages in my life, as I was facing a terrible and an unknown future filled with uncertainty. Most of my childhood was spent in the war, as I hardly remember my life before.

With the beginning of the Syrian crisis, my family and I fled to several cities including in Aleppo, then with the beginning of the terrorist organization ISIS’ attacks, we fled to the mountains in the city of Afrin in northern Syria where most of the Kurds had sought refuge. Later, my family was displaced to Beirut, Lebanon, in 2013 where we lived for the next 7 years. This period was spent between work, training workshops, and language classes. Beirut was one of the most important transformational points in my life, where my understanding of war, culture, and identity was shaped. I gained a deeper, instinctive insight into the significance of the homeland; a desire which still beats in my heart.

How did you discover your passion for art? What challenges have you faced as a Kurdish woman artist while still living in Kurdistan.

My passion for art began when I arrived in Britain in late 2019, when I finally had the freedom and security to engage in exploring my interests. My life and personal experience in the war, including the hardships and obstacles I faced, was the source of my inspiration in most of my paintings and sculptures. Also, my experience of displacement from one country to another was another source of inspiration, as different cultures and traditions opened my eyes to the differences in the Middle East. Fortunately, I didn’t start my artistic career in Kurdistan during the war and displacement, and I wasn’t painting at that time; but most Kurdish women artists face challenges in their artistic life, from lack of resources and materials to living difficulties, including the lack of income for artists in the region as one of the leading obstacles. Society’s inferior view of the art profession limits artists’ passion for their work, especially as a woman. Also, due to the regions’ lack of interest in art, most artists find challenges in building an audience for their exhibitions which limits artists’ encouragement to painting.

You are also a refugee who was displaced from Afrin. Tell us about why you left Rojava and how you arrived in Britain.

I left Rojava because of the lack of basic resources as a result of the civil war and the rise of ISIS in the region, which was one of the main causes for my family’s displacement to Lebanon. Also, because of the violation of the rights of the Kurds in the region by the Turkish government on the border, with which Rojava shares. In Lebanon and after 8 years my family and I had the opportunity to resettle in the UK, I think I was very lucky at that time to have a new opportunity to build a better new life. Many people did not have that opportunity and people, especially the Kurds in Rojava, continue to live with uncertainty and lack of safety while being constantly threatened by Turkish airstrikes and extremist organisations.

Your home city of Afrin has been under Turkish occupation since 2018. Your art presents strong and vivid images about war and displacement. Can you tell us a bit about this aspect of your art?

Unfortunately, after the Turkish state occupied the city of Afrin, the Kurds resisted in different ways. Some were standing on the front lines, some were rescuers in local organizations, some helped by publishing articles and research for prestigious universities and websites, which helped shed light on the issue. Others, like me, used the brush and white canvases as a form of resistance against the occupation to tell our stories. Kurdish artists such as Lukman Ahmad have been a strong source of inspiration for me. I think art can be a powerful tool and of great importance in shedding light on social issues such as war, displacement and oppressions and by bringing them to the world’s attention.

Art becomes a tool for raising awareness about the Kurdish cause, human rights violations, and other pressing concerns, both within the Kurdish community and in the broader world. Through my paintings, I endeavor to show the impact of war and conflict on people’s lives and their suffering after the traumas of these experiences. Displacement and escape are also other key themes that are heavily present in my art, having been personally affected by these subjects.

Pieces such as “Lost in Blue” and “Sanctuary” are deeply emotive and haunting images. Tell us about these pieces.

In these two paintings, I drew inspiration from a boat that sank on the Greek shores, claiming hundreds of lives. In 2015, with the tragic death of Alan Kurdi, the issue of the oppression and displacement of the Kurds as a result of the Syrian Civil War and the refugee crises collided dramatically. Unfortunately, the journey of asylum, which is not easy, has claimed the lives of thousands of refugees fleeing the war in search of a safe area. These subjects are very important for me to shed light on where many people continue to lose their lives through their asylum journeys while human rights organizations remain silent about the ongoing tragedy.

You recently had your piece exhibited at the Whitworth art Gallery in Manchester as part of the Refugee Week activities. Tell us about how you became involved in this exhibition and the pieces you contributed.

The Whitworth art gallery was conducting research with experts including doctors and researchers on the issue of the ‘Traces of Displacement’, as the name of the exhibition was. A friend of mine mentioned my name to the professor of History and Philosophy at the University of Manchester who was the project leader. After a meeting and interview, I was accepted as a participant in the research and the exhibition. Through this opportunity, I endeavored to focus on the Kurdish issue and the Turkish occupation of the region and their attempt to change its demography and abolish the Kurdish identity through a painting that embodied the Kurdish mountains, YPJ fighters, and the olive tree which is considered a sacred symbol in Rojava. Also, I participated in several other exhibitions since I arrived at the UK, including the Evelyn De Morgan exhibition at the Towneley Hall Gallery in Burnley, The Skelmersdale Art Network exhibition in Skelmersdale, and I also participated in the World Transformed Festival in Cornwall. Soon, I will be participating in the Afrin Fine Art Festival in Essen, Germany, which I am deeply excited about.

You also depict images of the Kurdish female fighters such as the YPJ in your art. How has your personal experiences of being a Kurdish woman determined your artistic representation of women?

Kurdish woman take on a leading role in the subjects of my paintings, as I try to present her strength, beauty, and courage from standing on the front lines in defense of her homeland and identity, to her expression of the beauty of the Kurdish heritage and culture. The Rojava Revolution and especially the Kurdish women fighting ISIS were for me a very great emotional and artistic source of inspiration, as I always saw in them a tremendous power that is not often difficult to draw or embody through a painting. Also, my aunt, who was one of these warrior women, taught me so much about the daily lives and the reality of these women. Through her courage and inspiration, I displayed the images of these women in exhibitions to the world. Moreover, by embracing gendered elements in my art, I bring to light the unique stories and challenges faced by Kurdish women in the diaspora. Their strength, resilience, and immeasurable contribution to their communities are captured through the vivid colors I use to represent their aspirations of freedom and empowerment, all the while being deeply and personally aware of the need to underscore Kurdish women’s need for inclusivity and gender equality in all facets of their lives.

How has the response been to your art, both in its Kurdishness and gendered elements, in the diaspora?

I think the response was very pleasant from the visitors’ comments and reactions to the exhibition organizers. What makes me most happy is people getting to know the Kurdish heritage and culture.

It is very delightful to see Kurdish art displayed in European and Western galleries, as it constitutes a very important imprint in building the Kurdish identity and transmitting it to future generations and help them connect with their roots, celebrate their heritage, and feel a sense of identity and belonging. Kurdish art in diaspora stands as a beacon of cultural resilience, keeping the flame of tradition and identity burning brightly amidst the challenges of displacement. It is a testament to the enduring spirit of a people, transcending borders, and time to celebrate and preserve the essence of Kurdish heritage.

What are your goals and aspirations for the future as a Kurdish woman and artist.

As a Kurdish woman and artist, my goals and aspirations for the future are deeply rooted in promoting and celebrating my identity and heritage while making a positive impact through my art. I aim to use my platform and art to empower women, highlighting their strength, resilience, and contributions to society. By showcasing their stories and experiences, I hope to inspire other women and break down societal barriers.

I look forward to completing my degree for higher academic stages, and I also aspire to participate in many national and international exhibitions through which I learn more about art. One of my many goals is also to work with humanitarian art organization where the proceeds of the paintings go to help and support women and children and everyone in needs in Rojava.

In summary, my future as a Kurdish woman and artist revolves around promoting empowerment, cultural preservation, advocacy, collaboration, education, personal growth, and art as a catalyst for healing and unity. I hope to make a lasting impact on the world through my creativity and dedication to the values I hold dear.

You can follow Vian Hussein’s art on her → Facebook and Instagram pages

Comments are closed.