To Remember is to Resist: The Jiyan Archives & Raz Xaidan

Interviewed by Matt Broomfield

“Resistance. Archiving, documenting, remembering, and referencing is an integral part of our continuing fight merely to exist as Kurds. To preserve is to accept, and in the absence of our own national archive, what we are doing at Jiyan is minuscule in comparison to what could be achieved if we as a collective society placed as much value in preserving the female voices of our stateless existence as we do for our men.”

— Raz Xaidan, founder of The Jiyan Archives

The Jiyan Archives, a self-directed, grassroots project documenting archival material of, by, and concerning Kurdish women throughout history, responds to an urgent need memorably identified by the intellectual Walter Benjamin. He draws a distinction between the linear, ‘historicist’ view of history, and his own particular interpretation of what Marx called ‘historical materialism’. To Benjamin, if one views the past merely as a linear “sequence of events like the beads of a rosary,” a fundamental dynamism is lost. He writes: “If one asks with whom the adherents of historicism actually empathize, the answer is inevitable: with the victor. And all rulers are the heirs of those who conquered before them.”

By contrast, to Benjamin then historical materialism implies not a crude, mechanistic understanding of the way history has advanced, but a dynamic, active engagement with the past which “grasps the constellation [our] own era has formed with a definite earlier one.” Benjamin’s materialism calls for an active engagement with a living history, understood as inextricably bound up with our political present.

Nowhere is this need more urgent than in the case of the Kurdish people, and particularly Kurdish women. As Jiyan Archives founder Raz Xaidan says: “Archiving, documenting, remembering, and referencing is an integral part of our continuing fight merely to exist.”

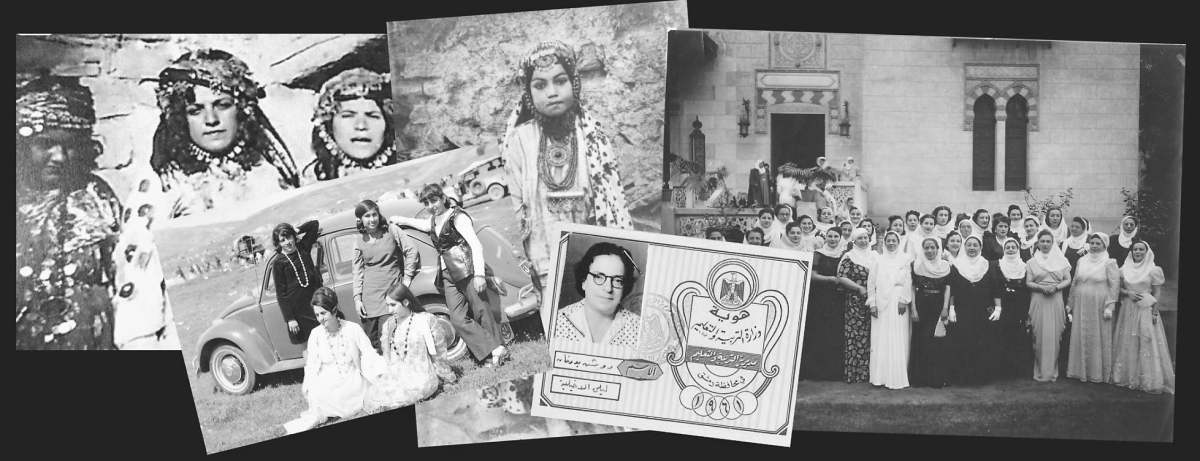

Kurdish women’s history has long been told for them – and reduced to a mere sequence of war, genocide and tragedy, in a narrative of defeat which denies the complex nexus between past life struggles and present reality. As a stateless people, the Kurds have been denied access to or control over conventional, historicist narratives. But this also creates space for Kurdish archivists to recreate their own history, “filled with art, literature, diplomacy, music and special characters” whose contributions, when preserved and recorded, reveal the existence of historic forces the Kurds’ enemies have been unable to repress until this day.

Hence The Jiyan Archives mingles historical material contributed by Kurdish women and others across the globe, obituaries, and interviews with women living in Kurdistan today. As the very name Jiyan (‘Life’) suggests, the Kurdish archivist is necessarily and keenly aware of history as a dynamic, living force.

I conducted the following interview with Raz Xaidan, which has been lightly edited for clarity.

How and why did The Jiyan Archives project begin? What are your major achievements thus far?

Personally, I have always been invested in Kurdish archives. As a multi-disciplinary creative, I had incorporated archival documents and photographs into my multimedia art pieces for many years. As I was based in South (Iraqi) Kurdistan for quite some time, I also had the privilege of visiting old antique houses and markets where I would spend my weekends digging (literally through dirt) to rescue lost photographs and items that were just left to rot. My personal connection to our past, along with seeing the disconnect in Kurdish society between our archives and the role [the past] plays in our resistance, really speared me to re-evaluate how I can use my creative skillset and admiration for the past to create a purposeful space to home my findings.

The Jiyan Archives was launched in August 2021, with the sole purpose of establishing a collaborative platform that highlighted and documented the lives and stories of Kurdish women. The majority of archives that already existed online are heavily focused on Kurdish men, or content related to war and genocides – I wanted to establish a platform that paid homage to our women, whether they were noble, local, or a matriarch. In the summer of 2021, I sat in my studio in Hewlêr (Erbil) and began drafting ideas, names for the project, and thinking of matriarchal figures to interview.

I am grateful to have established a strong network of versatile Kurdish women who were so helpful in guiding me with contacts, or details of the women I wanted to interview. That summer I also appointed two young Kurdish women to intern and spend their summer with me growing their creative skills in the studio. On their first day, their first task was to visit and conduct an interview with Sînemxan Bedirxan, known as the last princess of Kurdistan – a super cool first day for the gang in the studio!

The true initial success of the creation of The Jiyan Archives was not me building the platform, it was seeing how a young Kurdish girl could connect to a matriarchal figure with such a powerful life story – one which she had not been previously exposed to. It was witnessing in real time the effect and educational potential this project could have in connecting the younger Kurdish generation to the older one, in a collaborative approach which has been our biggest success.

What does a typical work week look like?

The Jiyan Team consists of 11 volunteers (myself included). We are scattered across five continents. Every item, archive, article, and story from the platform has been kindly donated in time and effort by our selfless team. A typical work week will consist of checking submissions from the kind public who submit their personal archives to us directly for consideration and inclusion, editing articles, and discussing potential women to highlight. We are self-funded, which means we work on our own terms.

What is the particular need for an archive for a ‘stateless’ people? What’s the relationship between the preservation of Kurdish history, and the political status of the Kurds?

Resistance. Archiving, documenting, remembering, and referencing is an integral part of our continuing fight merely to exist as Kurds. To preserve is to accept, and in the absence of our own national archive, what we are doing at Jiyan is minuscule in comparison to what could be achieved if we as a collective society placed as much value in preserving the female voices of our stateless existence as we do for our men. It’s right that our men [have their voices preserved], but what became of the women who birthed them? ‘Stateless’ is an ugly hand that we’ve been dealt, but not every detail of our past is filled with doom or the theft of our [land]. Away from tragedy and war, we have a rich history filled with art, literature, diplomacy, music and special characters to treasure and be inspired by.

How does the fact you are recording the history of a non-state people affect the way you work, what you choose to record, and how you gather material?

We purely focus on documenting the lives and stories of Kurdish women, whether they were or are in Kurdistan or based in the diaspora. Although 95% of our interviews are conducted in Kurdish, we lead with English as the first language on the platform to support the ideal of educating and enlightening global readers on the women we highlight and the archives we digitise. Every item in our archive has either been scanned by myself or submitted by users of the site. We have a very laid-back approach when conducting interviews with the women we platform; transparency and authenticity is key for us, the platform does not exist to sensationalise female voices, and nor do we engage with the usual tripe we see online that empowers the fetishized gaze of Kurdish women. We tend to let the women lead us in interviews, as it is their story being told – and often during home visits we experience typical Kurdish hospitality, where we are fed before we leave!

Similarly, what is the particular need for archives preserving women’s history? Are there aspects of your working process you would characterise as feminist or affected by the fact you focus on women’s history?

To expand on some ideas mentioned in my previous answer – we are a 100% a feminist platform. If there was a already space that existed for Kurdish women and their archives to be celebrated without political or religious [influence], we would not exist. Rather, the absence of such a platform is why Jiyan was created. There is no equal playing field when it comes to our documented history. Personal archives are very intimate items. Many overlook how challenging it can be to obtain personal archives from Kurdish women; we still live in an era where many Kurdish societies and communities are controlled by taboo and stigma.

Are there regions of Kurdistan or periods of history you have been able to gather more or less information about, and why? What aspects of your archive would you like to deepen and expand in the future?

Whilst the region was overflowing with Western photographers in the early 1900s, this period is our most difficult when it comes to sourcing local material. Photographs exist – but who owns it? Where was it taken? What was the year? All this remains a mystery due to factors such as conflict and lack of data or records.

We introduced a section on our page, ‘The Unclaimed Archives’, which allows us to share archival material in the hope we could find its owners through people sharing the material; sometimes we would be successful, other times not so much. Through our collaborative platform on our site where the public can upload their personal items to us, our most popular region has been Rojava (Western Kurdistan), with particular focus on the Afrin region. Second to Afrin would be Silêmanî in Bashur (Southern Kurdistan). Currently we would like to integrate more archival submissions from Bakur (Northern Kurdistan), although our writers have interviewed and highlighted some incredible women from the region. We also have the first online Kurdish Women’s Obituary which is currently a priority for us to invest more time in. This section is very special to us but understandably, not the easiest to write for.

You can follow Raz Xaidan’s work at her

→ Website, Twitter, Instagram, and Jiyan Archives pages

Comments are closed.