Archaeological Heritage Crimes in Occupied Afrin

By David Neurdenburg & Szymon Jazowski

I. Background

Since 2011, cultural heritage in Syria has been under constant threat. Even though the civil war has raged on for more than a decade, there is still no end in sight. The involvement of various foreign actors has further complicated the country’s ongoing division between several rival factions. With around 5.2 million Syrians internally displaced, 6.8 million fleeing the country, the destruction of much of the country’s infrastructure and economic assets, and a death toll of well over 500,000, life within the country has become exceedingly difficult.[1][2]

With the country in chaos, museums and heritage sites became the targets of looting and purposeful destruction. Motivated in part by financial gain, as well as a reaction against the Assad government, which had effectively appropriated the imagery of the region’s past to bolster its own image, almost all museums in Syria were targeted by civilians and militias alike.[3] The looting of archaeological sites in cities and the countryside, which already took place in a limited fashion before the start of the war, also skyrocketed.[4]

The world watched with bated breath as various groups got close to securing complete control of the Syrian territory, with the rapid rise of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) being perhaps the most infamous. Arriving from neighbouring Iraq in 2013, it swept across the country, ISIS instituted a brutal and repressive regime in the areas it controlled. As it advanced towards the northern borders of Syria, causing hundreds of thousands to flee, it would be met with fierce but ultimately unsuccessful resistance. It was only during the battle over the border town of Kobanê in 2014 that the group would suffer its first major defeat at the hands of Kurdish militias, the male YPG (People’s Protection Units) and female YPJ (Women’s Protection Units), turning the tide in the war against ISIS.[5]

ISIS’s brutality was broadcast in the global press as the group purposefully spread images of its public executions and a myriad of other crimes. Notable among these was the targeted destruction of famous monuments and museums, which were claimed to be a form of idolatry. One of the most notable examples was ISIS sacking of Palmyra.[6]

Afrîn & the “Rojava Revolution”

The north-western district of Afrîn had been spared much of the chaos and destruction of the Syrian Civil War. The city of Afrîn — inhabited predominantly by Kurds, but also Arabs and Turkmen — had become a haven for internally displaced people (IDPs) seeking reprieve from the conflict.[7]

Power transitioned from the Assad government to local assemblies with little to no bloodshed, with government troops leaving the city following growing public demonstrations in 2012. In its place, the inhabitants of Afrîn would attempt to set up their own system of local self-governance.[8] In 2014, the “canton of Afrîn” declared its autonomy, alongside the cantons of Kobanê and Jazeera towards the east. In 2016, they declared the Democratic Federation of North-East Syria to unite the various peoples that inhabit the now-autonomous regions of Syria.[9] Its armed forces — consisting of Kurdish, Arab, and Assyrian militias and opposition groups — are known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Often colloquially referred to as the “Rojava Revolution”, after the name for the predominantly Kurdish areas of Syria (i.e. Western Kurdistan), it based itself on principles such as direct/grassroots democracy, cooperative economics, and women’s liberation. The extent to which these ideals were implemented was not always equal across the board, and much has already been written about the workings of the democratic system in North-East Syria.[10][11][12][13]

However, major advances were made with regards to gender equality, democratic participation, and peaceful coexistence between the North-East’s diverse ethnic and religious groups. The implementation of the co-chair system, requiring the equal division of representation between men and women within committees, councils, and communes, became one of the most recognisable features of the Democratic Autonomous Administration, as it is now called.[14]

In contrast to decades of rule from Damascus, the autonomous administration’s confederal system of democracy emphasises regional autonomy in a way that was previously seen as impossible. Rather than favouring one ethnic group as was done by the pan-Arabist Ba’athist ideology of the government, there is a heavy emphasis on Syria being constituted by many different peoples — Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, Turkmen, Armenians, Circassians, and Chechens — plus religions, such as Muslims, Christians, Alevis, and Yazidis.[15]

While the Kobanê and Jazeera cantons experienced major destruction of infrastructure and urban centres during the war against ISIS, Afrîn would remain peaceful and relatively economically stable up until 2018. However, this would drastically change during the Turkish invasion and subsequent occupation of the region.

II. Turkey and Operation “Olive Branch”

As mentioned previously, the Syrian Civil War has, since its beginning, seen the involvement of various regional and international actors. Neighbouring Syria to the north, the Turkish state has been extensively involved in the civil war since its beginning, backing a number of armed opposition groups that constituted the anti-Assad “Free Syrian Army” (FSA) that formed in 2011. While the FSA’s goal was to overthrow the Assad government, internally, opinions were divided as to how a new Syria should be governed, especially between secular and Islamist groups.[16]

When the FSA’s initial successes against government forces waned in 2012, various Islamist groups filled the gaps left by the retreating Syrian government and the disorganised opposition. These groups ranged from Salafist groups such as Jaysh al-Islam and Ahrar al-Sham and the radical Jihadist groups such as Jabhat al-Nusrah and the Islamic State.[17] Following the rapid rise of ISIS, few of the original opposition groups survived, with the mantle of the FSA being claimed by several groups. Turkey continued to fund, arm and train Salafist groups such as Ahrar al-Sham, as well as factions of the fractured FSA. In 2017, the Turkish-aligned groups would rebrand themselves as the Syrian National Army (SNA).[18][19]

Turkey’s relation to the Democratic Federation of North-East Syria were hostile from the start, motivated by its own domestic Kurdish insurgency and fears of a Kurdish political entity on its southern border. Ever since the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the Kurdish population in the southeast of the country (Northern Kurdistan) has faced political persecution, assimilation policies and multiple cases of ethnic cleansing.[20][21][22] Both political and armed resistance, which took several different forms over the past century, were met with heavy-handed repression, and the conflict continues at a low intensity till today.

From August 2016 to March 2017, the first substantial Turkish military intervention was undertaken north of Aleppo, Operation “Euphrates Shield.” Targeting both ISIS as well as the SDF, who were also engaged in combat with ISIS, they would clear a corridor towards the city of Al-Bab. This newly established foothold in Syria would also isolate the canton of Afrîn from the rest of the Democratic Federation of North-East Syria.[23]

Effectively an enclave, Afrîn remained under the control of the SDF for little under a year, after which the Turkish army and aligned groups of the SNA commenced Operation “Olive Branch” on January 20th, aiming to push out the SDF and the local civilian administrative structures.[24] Isolated, outnumbered, and outgunned, it did not take long for the Turkish army and its affiliated armed groups to take over vast swathes of the district of Afrîn. When the Turkish army threatened to surround the city of Afrîn in March, rather than engaging in prolonged urban warfare, the SDF retreated from the city to avoid its destruction. After fifty-eight days of the operation, the city was now fully occupied by the SNA and Turkish army.[25][26]

The Turkish-backed occupation of Afrîn instigated the displacement of much of Afrîn’s Kurdish population. Following the takeover of the city, in April 2018, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that around 137,000 people had fled the region as a result of the occupation.[27] In February 2023, Syrians for Truth and Justice wrote of an estimate between “137,070 and 320,000.”[28]

Following Turkey’s successful campaign in Afrîn, a second operation took place further to the East in 2019, named “Peace Spring”, occupying a strip of land 30 kilometres into Syria including the towns of Serê Kaniyê (Ras Al-Ayn) and Girê Spî (Tell Abyad).[29]

The SNA & Human Rights Violations in Afrîn

The Syrian National Army, which came into being in 2017, is a Turkish-backed coalition of opposition groups located primarily in the northwest of Syria. It consists of former FSA formations, such as the Al-Hamza Division and Liwa 51, Turkmen militias such has Furqat al-Sultan Murad, as well as Salafist groups such as Ahrar al-Sham, Ahrar al-Sharqiya, Al-Jabha Al-Shamiya and Jaysh al-Islam.[30] Since the occupation of Afrîn, they have also been the primary occupying and governing force of the region, splitting the territory between the 15 different constituent groups. Complicating matters further is the continual infighting between these different armed factions, leading to civilians getting caught in the crossfire.[31][32]

Other than the displacement of much of Afrîn’s native population, those who remain are subjected to harsh and arbitrary rule. The occupation of civilian homes and buildings, dismantling and looting of industrial equipment and the ransacking of olive groves are well-documented and constitute a major economic impact of the occupation, but the SNA has also become infamous for its human rights violations committed against those who remain.[33][34][35] Sexual abuse, forced conversions of Yezidis, kidnappings, extrajudicial imprisonment, and executions were noted by the United Nations and various Syrian human rights organisations.[36][37][38] Afrîn’s Kurdish and Yezidi populations have been the primary targets.[39]

III. Archaeology in Afrîn

Whilst all of the international excavation teams working in Syria left the country following the start of the Syrian crisis, many Syrian archaeologists had no other option but to remain. Many risked their lives to safeguard the country’s heritage and their life’s work as territory changed hands between different factions.

In Afrîn, after the relatively peaceful transition from the Assad government to the local autonomous administration, archaeologists from the region formed a new antiquities directorate as part of the city’s culture and heritage committee in 2014. Consisting of equal parts men and women, they would set about preserving and monitoring sites within the district. As is prohibited in article 9.1 of the 1999 second protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, no excavation work would be undertaken. The work of the antiquities directorate would instead be limited to the monitoring and preservation of sites, outreach initiatives and seminars. Prior to the civil war, Syria’s antiquities ministry had registered 56 sites within the district of Afrîn. As part of the fertile crescent, the Afrîn region is home to sites belonging to a rich variety of cultures.

Article 9 – Protection of cultural property in occupied territory

- Without prejudice to the provisions of Articles 4 and 5 of the Convention, a Party in occupation of the whole or part of the territory of another Party shall prohibit and prevent in relation to the occupied territory:

(a) any illicit export, other removal or transfer of ownership of cultural property;

(b) any archaeological excavation, save where this is strictly required to safeguard, record or preserve cultural property;

(c) any alteration to, or change of use of, cultural property which is intended to conceal or destroy cultural, historical or scientific evidence.

— Second Protocol to The Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

One of the earliest and most notable sites is that of the Dederiyeh Cave, which housed two skeletons of Neanderthal infants, seemingly intentionally buried. In the cave, approximately 15 individuals were found in total. Various lithic tools were also present within the cave, most closely resembling those of the Mousterian culture.[40]

The Afrîn region has been within the sphere of influence of various different cultures and empires, including the Hurrians, Hittites, and Assyrians.[41] During Afrîn’s integration into the Hittite Empire, the Iron-Age temple of Ain Dara was constructed — one of the most famous sites in the entire region. Afterwards, the region passed through periods of rule by the Aramaic, Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, and Achaemenid empires. Following Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid empire, and the subsequent division of his empire into various successor states following his death, Afrîn was ruled by the Seleucids.[42] The ancient city of Cyrrhus, founded in 300 BC by Seleucus I Nicator, is closely associated with this period. The site itself also demonstrates the different occupations of the area in the subsequent centuries by Romans, Byzantines, and Muslim dynasties.[43]

Heritage Violations in Afrîn

Since the occupation of Afrîn, heritage sites in the region have become targets for the factions of the SNA, either for monetary gain or to purposefully erase the multicultural history of the region. Whilst these violations have been confirmed by various international bodies, little has been done to condemn and prevent further infractions.[44][45][46] Within academic circles, the topic of the state of northwest Syrian archaeology has also gone under-analysed, even though the threat to tangible heritage in Afrîn is a current one.

In practice, the SNA factions committing these acts have been able to act with near full impunity. This is worsened by the lack of transparency on the state of heritage sites in Turkish-occupied Afrîn; much of the work undertaken to document the violations was done through open-source intelligence (OSINT), satellite imagery, and informant networks. Since the 2018 occupation, the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate has documented violations at 41 different sites. In some cases, the violations are more blatant, with SNA media outlets airing live-fire drills inside of ruins or during illegal excavations, perhaps not realising that these actions are against the 1954 Hague Convention. This was infamously the case with the temple of Ain Dara.

“38. While attacks on cultural heritage in the course of the conflict have largely been associated with ISIL and their destruction and pillage of archaeological sites, the Commission also documented attacks carried out by Ahrar al-Sham on the thirteenth century citadel in the old city of Aleppo and the bulldozing, looting and destruction of archaeological sites and Yazidi shrines and graves by the Syrian National Army in Afrin.”

— Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, A/HRC/46/54

Within the SNA, Jihadist and Salafist groups have made use of this level of impunity to target religious minority groups within Afrîn, most notably the Yezidi community. There is a long-standing slanderous historical misconception that the Yezidi religion is a form of “devil worship,” which has been weaponized by various Islamist factions.[47] By forcing Yezidi practices underground, and through coerced conversions, the centuries-old Yezidi presence in Afrîn is being slowly erased. Out of the approximately 18 shrines located within Afrîn, at least 9 have been destroyed.[48]

To illustrate these heritage violations, we can take a look at two specific case studies of prominent local sites that best demonstrate the activities of the SNA and occupation: the ruins of the city of Cyrrhus and the temple of Ain Dara.

The Ancient City of Cyrrhus

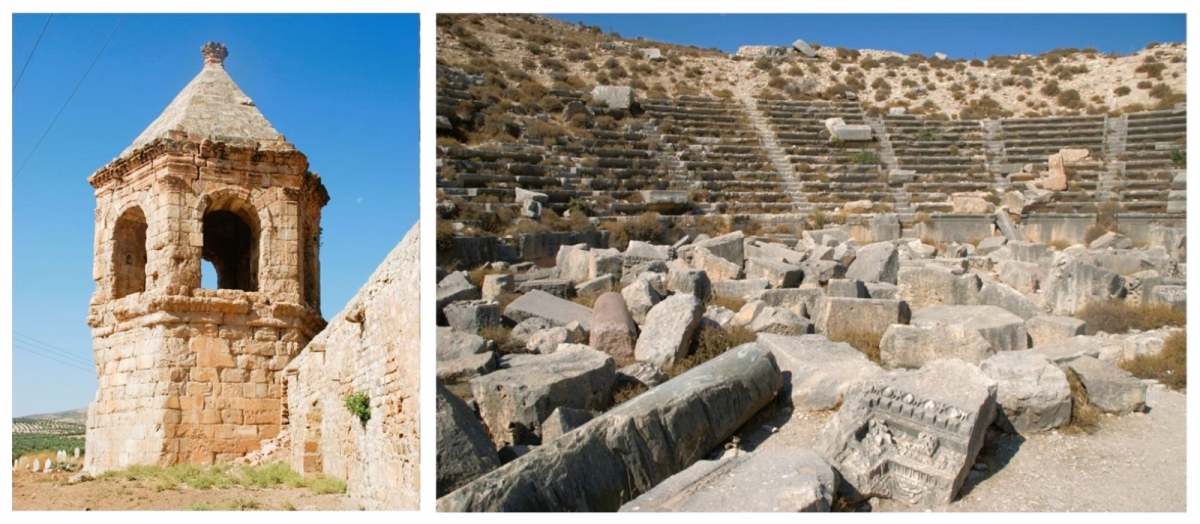

The city of Cyrus, known in modern times as Nabi Hori, is a large archaeological site in the north of Syria. It is located 30 km from the centre of the city of Afrîn. Cyrrhus was founded around the year 300 BC, during what is known as the Hellenistic period, by Seleucus I Nicator, one of the generals and successors of Alexander the Great. The city remained inhabited and expanded during the Roman period until the 3rd century AD, when it was abandoned. It was then re-occupied between the 4th and 5th century AD. In the 6th century AD, it was taken during the Islamic conquest and then reconquered by the Byzantine forces in the 10th century. The city’s history ended with the Seljuk invasion led by Nur al-Din Zangi’s in the 12th century AD.[49]

The first excavations at the site of Cyrrhus were carried out in 1952 by an archaeological team led by Edmon Frizol. These excavations were later expanded in 2006 by the Lebanese archaeological mission headed by Jeanine Abdul Massih. Since then, the French and Lebanese missions were doing research in cooperation on the site of Cyrrhus. They studied the city’s fortifications, the Roman Theatre, the Necropolis, and the layout of the city streets and their changes throughout the site’s occupation phases.[50]

The plan of the city in the Hellenistic period follows the rectangular chess grid. The grid is centred on a main colonnaded street running from north to south. During the Roman period, city planning did not change except for the realignment of the axis of the city by adding another main street running from east to west. The Byzantine period saw no changes to the city planning, and it was thought that it did not change during the Islamic Period as well, but this was called into question during the 2007–2009 excavations. Unfortunately, a deeper understanding of the city layout during the Islamic period remains out of reach.[51]

The most monumental part of the ancient city of Cyrrhus is the Ancient Roman Amphitheatre. It is dated to the 2nd century AD, with some elements of decoration added later in the 3rd century AD. It is the second-largest Roman theatre in Syria, with a diameter of 120m, second in size only to the theatre in the ancient city of Apamea. The stage is 48 m in diameter and surrounded by 24 rows of seats arranged in a half circle. The lower seats are unique since they feature names carved onto them, seemingly to mark permanent reservations. These seats are also adorned with sculpted dolphins. The courtyard of the theatre is filled with columns decorated with friezes.[52]

Another feature of interest in the city of Cyrrhus is the Pyramid Burial site. Located outside the city gates, the tomb is hexagonal in shape and in the form of a tower and it is dated to either the end of 2nd century AD or the beginning of 3rd century AD. This form of tomb is unique to the region and period. The tower consists of two floors, the bottom floor is reserved for the burial and the top floor is accessed through a stone staircase. The upper section is surrounded by windows on all sides that overlook the landscape. There are 6 columns inside the tomb with decorative Corinthian friezes and lion masks that represent the god Zeus. The lower hall is accessed by a small doorway that leads into a rectangular room with the burial, and the entrance door is decorated as well. Later on, during the Mamluk Period, the tomb was attributed to Sufi Prophet Hori and a mosque was built next to the tower.[53]

The city of Cyrrhus had 4 bridges connecting it to the road systems of the region. Two of these bridges survive today. The biggest one is the bridge located on the eastern side of the city, which measures 120 m and consists of 6 arches. This bridge was renovated by the Directorate of Antiquities of Aleppo. While the renovations were not up to standard and are clearly distinguishable from the original bridge, they were necessary to maintain its structural integrity. One kilometre away from the larger bridge, there is another smaller bridge that passes the river Afrîn. This bridge consists of 3 arches and is 92 m long.[54]

The site of Cyrrhus was one of the first archaeological sites affected by the Turkish occupation, as it is very close to the Syrian-Turkish border. In the initial stages of Operation Olive Branch, the site was bombed. Following the bombardment, Turkish army and SNA presence were established at the premises of Cyrrhus. Later actions were difficult to trace as the military maintained strict oversight at the site and did not allow anyone to approach. Despite that, images and videos confirming suspicious activities surfaced, evidencing the movement of heavy machinery, including bulldozers and excavators, at the site.[55]

The occupying forces built prefabricated buildings and set up tents on the outskirts of the site, and clear evidence of looting emerged. Images of pits all over the city of Cyrrhus were taken. These pits show a clear intention of removing artefacts from the site as well as the visible destruction of archaeological layers. Some of the photos show the improperly excavated Roman mosaics. These actions were conducted by the Turkish backed militias under Turkish army supervision.[56]

Satellite imagery shows the staggering scale of the destruction of Cyrrhus. Prior to the Turkish occupation, the site remained largely unexcavated, but during the period of the occupation, it is visible on satellite images that the site became covered with pits spanning almost the entirety of the ancient city and its necropolis.

The mosque attached to the ancient tomb at Cyrrhus was remodelled by the occupation forces after their arrival. Early evidence of suspicious activity includes photos of prefabricated buildings, indicating setting up of a construction site. Later in 2018, the first pictures of the rebuilding of the wooden balcony became available. In 2020, photos of scaffolding, further indicating a clear intention of construction, were taken. On December 22, 2022, photos showcasing the full extent of the remodelling of the mosque became available. Any rebuilding of heritage sites by occupying forces is in clear violation of article 9.1 of The Hague Convention.

The work on the mosque specifically is not accidental either, as it is the only Ottoman Period feature in the city of Cyrrhus and the work done on the balcony, flooring, and pulpit of the mosque show a clear intention to distort it more towards the Ottoman style of architecture than it originally was.[57]

The ancient city of Cyrrhus is a valuable and, in many ways, unique site of the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic periods. It features many monumental pieces of architecture. Most importantly, it remains largely unexplored by the scientific archaeological community. Unfortunately, this will not be possible to the same extent as before due to the thorough looting and destruction.

The Temple of Ain Dara

Ain Dara is a site located 8 km south of the city of Afrîn in northern Syria. This site dates to the Neolithic period in its earliest layers and to the Middle Ages in the most recent archaeological layers. The settlements that were present at the site were not particularly large. Notably, during the Late Roman era, the settlement was walled off. Only the foundations of these fortifications were preserved in modern times. During the Byzantine and Islamic periods, the city’s fortifications were expanded, the wall was renovated, and square towers were added.[58]

The most interesting feature of the Ain Dara site is its temple. It was discovered in a great state of preservation, with almost all of the lower sections of the wall as well as the flooring present. This gives a very clear impression of how the temple looked and changed over time.

The temple was excavated in 1956 for the first time by the General Department of Antiquities and Museums in Damascus, under the leadership of F. Seirafi. Then the excavations were interrupted in 1964 and resumed in 1976, headed by A. Abu Assaf. The settlement was excavated by an American team between 1982-1984 under the direction of E. Stone and P. Zimansky. The temple also underwent conservation done by a Syrian-Japanese team led by H. Hamadeh and T. A. Sawa. The restoration was concluded by a final report published in 1997.[59]

The temple at Ain Dara dates to the end of the second millennium BC and the beginning of the first millennium BC. The temple is described as Syro-Hittite in style since it has a typical plan for Levantine temples, but the decoration of the temple is in the early Imperial Hittite style. This is due to the fact that the temple was modified later, during the Hittite conquest of the area. The end of its use is thought to have been the destruction and burning of the temple by the Neo-Assyrian King Tiglat-Pileser III during his reign between 745-727 BC.[60]

The plan of the temple follows the common style in the Levant at this period, called in antis. This type of temple is characterised by a simple internal plan with a single entrance, one room at the entry and a sanctuary room with a single entrance. The now visible sanctuary building was not the only feature of the larger temple complex, which included a large basalt and limestone-lined courtyard, a well, and a basin, all of which are archaeologically attested. A unique feature of the temple are the carvings of human steps on the thresholds of the two rooms. The carvings in the room show the left foot stepping forward, while the carvings on the threshold of the sanctuary show the right foot stepping forward. This is thought to either represent the footsteps of the god worshipped in the temple leading into the sanctuary or instructions for the worshippers on how to enter the temple. Both explanations could be valid at the same time as well.[61][62]

Another notable feature of the temple is the carved basalt lion. It was found in an exceptional state of preservation, with just a part of the left ear missing. It is 2.5 m long and 80 cm wide; the height of the statue is 2.7 m; and it weighs 12 tonnes. This type of lion sculpture, especially in this state, is rare. Although similar statues in the Hittite imperial style were found in the city of Hattusa in Anatolia, the statue guarded the entrance to the temple and was accompanied by another statue of a lion on the other side of the doors.[63]

The carvings inside the temple represent scenes of gods from Hittite and Levantine mythology. The most notable examples are the carvings of the storm god Shaushga, a local iteration of the Near Eastern goddess Ishtar. The storm god is depicted as wearing a horned crown, his hands outstretched in command of lightning, and he wears a sword at his belt and pointed shoes. All of these features are characteristic of Hittite depictions of the storm god, especially recognisable for the Hittite style are the pointed shoes. The depiction of Shaushga also follows the Hittite style, she appears naked, holding a staff, and wearing pointed shoes. The relief and sculptural depictions are firmly Hittite, and it is difficult to find any Syrian-Levantine elements in them, but the form of the temple is undeniably Levantine, making Ain Dara a very interesting case of cultural blending within the border zone between Anatolia and Levant.[64][65]

The temple at Ain-Dara was severely destroyed during the Turkish occupation. The first part of the destruction took place during an air raid on the 21st of January 2018. Explosions damaged the main entrance to the temple, the second and first terraces of the artificial hill it stands on, and the sanctuary building itself. The reliefs that were discussed previously were destroyed and their fragments were scattered on the floor of the temple. The famous and unique steps on the thresholds of the temple were destroyed and are now impossible to restore. Buildings surrounding the temple remained largely untouched during the air strike, indicating the intentionality of the destruction of the ancient site of Ain Dara. 50-60% of the previously exceptionally preserved temple is now destroyed.[66]

The violations of the site did not stop after the airstrike as the occupation forces proceeded to loot the ancient temple and its surroundings. On the 11th of July 2019, Turkish forces as well as militias supported by Turkey began the process of destructive excavations. These were conducted using heavy machinery like bulldozers and excavators with no regard for proper archaeological methods, which in turn irreversibly destroyed the archaeological layers of the site. The basalt lion at the entrance to the temple was stolen and reportedly transported to Turkey alongside the previously undiscovered mirror statue of the basalt lion, which was found during the looting. The looting did not pertain only to the acropolis and the temple of Ain Dara, but to the lower city as well, which had remained largely archaeologically unexplored. Due to the looting, it will be impossible to carry out further research on the lower city in the future.[67]

In September of 2019, fighters affiliated with the Turkish-backed “National Front for Liberation” staged a live-fire exercise within the temple, using rifles, grenades, and rocket-launchers in a mock-assault on the temple. This assault was broadcast on Nedaa’ Syria, an SNA-affiliated media outlet, even though this action was in blatant violation of international antiquities law.[68]

The site of Ain Dara is a unique site on a world-wide scale thanks to its temple, and one of the most important sites for the region of Afrîn due to its monumentality and archaeological value. Unfortunately, due to the actions undertaken by the Turkish occupation forces, the information that this site contained about the past of the region was irreparably destroyed.

IV. Conclusions

During the occupation of Afrîn, SNA-affiliated militias and the Turkish army have committed numerous violations, not only with regards to the heritage of the region but also towards the civilian population, which has been previously documented by The Kurdish Center for Studies.[69] The international response to this has so far been limited, even though the Turkish state bears the responsibility of reigning in its proxy-groups in Syria whilst adhering to the relevant international agreements.

Even though the Turkish military might shirk accountability because the bulk of these crimes were committed by the SNA, this would not be in accordance with international regulations surrounding the responsibility of safe-guarding heritage. Looted artefacts found by the Turkish border only increases the culpability of the Turkish state in these heritage crimes.

“Being convinced that damage to cultural property belonging to any people whatsoever means damage to the cultural heritage of all mankind, since each people makes its contribution to the culture of the world;

Considering that the preservation of the cultural heritage is of great importance for all peoples of the world and that it is important that this heritage should receive international protection;”

— Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention

The 1954 Hague Convention’s preamble summarised concisely why such international regulations are important. It is in light of this reasoning that the violations that are taking place today can hardly be ignored, or that this is an issue that can be postponed until after a hypothetical resolution to the Syrian crisis. Whilst it may already be too late to recover much of what was lost since 2018, this does not preclude the possibility of increased international involvement in the case. Relevant international bodies, academics, and those with a love of the past should be paying more mind to this case. ISIS’ destruction of heritage was well published due to its brazen propaganda, but a silent campaign of destruction deserves just as much attention.

The Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention outlines in detail the various steps that any party in a conflict must undertake in order to safeguard tangible heritage and cultural property. This is a process that must be undertaken regardless of political or military reasoning. In practice, few of these were undertaken and many of them were flagrantly disregarded.

Remaining silent in the face of all this means capitulation to nationalist and state interests that run counter to the entire ethical foundation of the discipline. It also means, as archaeologists and concerned citizens, the abandonment of the people of Afrîn and the connection they hold to their heritage. A heritage that archaeologists from Afrîn continually emphasise is not just the heritage of Kurds or Arabs, or of Muslims or Christians, but of all components of the region and humanity at large.

References

[1] “Syria situation” (2023). United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. link

[2] “Behind the data: Recording civilian casualties in Syria” (2023, May 11). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. link

[3] Jones, C.W. (2018). Understanding ISIS’s Destruction of Antiquities as a Rejection of Nationalism. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies, 6(1-2), 31-58.

[4] Casana, J. & E.J. Laugier (2017). Satellite imagery-based monitoring of archaeological site damage in the Syrian civil war. PLoS ONE, 12(11).

[5] Knights, M. & W. van Wilgenburg (2021). Accidental Allies: The US-Syrian Democratic Forces Partnership Against the Islamic State. I.B. Tauris. p. 63.

[6] Lababidi, R. & H. Qassar (2016). Did They Really Forget How to Do It? Iraq, Syria and the International Response to Protect a Shared Heritage. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies, 4(4), 341-362.

[7] Schmidinger, T. (2019). The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds: Self-Determination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Afrin Region of Rojava. PM Press. p. 4.

[8] Ibid. p. 49.

[9] Ibid. p. 50, 53.

[10] Allsopp, H. & W. van Wilgenburg (2019). The Kurds of Northern Syria: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. I.B. Tauris. p. 215.

[11] Hammy. C, & T.J. Miles (2021). Lessons From Rojava for the Paradigm of Social Ecology. Frontiers in Political Science, 3.

[12] Rojava Information Center (2019). Beyond the Frontlines: The Building of the Democratic System in North and East Syria. link

[13] Schmidinger, T. (2018). Rojava: Revolution, War and the Future of Syria’s Kurds. Pluto Press.

[14] Şimşek B. & J. Jongerden (2018). Gender Revolution in Rojava: The Voices beyond Tabloid Geopolitics. Geopolitics, 26(4), 1023-1045.

[15] Allsopp, H. & W. van Wilgenburg (2019). The Kurds of Northern Syria: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. I.B. Tauris. p. 215.

[16] Rabinovich, I. & C. Valensi (2021). Syrian Requiem: The Civil War and Its Aftermath. Princeton University Press. p. 47-48.

[17] Ibid. p. 49.

[18] European Union Agency for Asylum (2023, February 7). Country Guidance: Syria (February 2023). pdf

[19] Rojava Information Center (2022). The SNA Encyclopedia: A Guide to the Turkish Proxy Militias. pdf

[20] Bruinessen, M.M. van (1994). The Suppression of the Dersim Rebellion in Turkey (1937-1938). In G.J. Andreopoulos (Ed.), Conceptual and Historical Dimensions of Genocide (pp. 141-170). University of Pennsylvania Press.

[21] Jongerden, J. (2005). Villages of No Return. Middle East Report, 235. link

[22] Yegen, M. (2009). “Prospective-Turks” or “Pseudo-Citizens:” Kurds in Turkey. The Middle East Journal, 63(4), p. 597-616.

[23] Knights, M. & W. van Wilgenburg (2021). Accidental Allies: The US-Syrian Democratic Forces Partnership Against the Islamic State. I.B. Tauris. p. 128.

[24] Schmidinger, T. (2019). The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds: Self-Determination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Afrin Region of Rojava. PM Press. p. 83.

[25] Allsopp, H. & W. van Wilgenburg (2019). The Kurds of Northern Syria: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. I.B. Tauris. p. 126.

[26] Knights, M. & W. van Wilgenburg (2021). Accidental Allies: The US-Syrian Democratic Forces Partnership Against the Islamic State. I.B. Tauris. p. 168-169.

[27] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2018). Afrin Displacement: Facts and Figures. link

[28] “Syria: Complaint to Eight UN Special Rapporteurs about Torture in Afrin.” (2023, February 2). Syrians for Truth and Justice. link

[29] Knights, M. & W. van Wilgenburg (2021). Accidental Allies: The US-Syrian Democratic Forces Partnership Against the Islamic State. I.B. Tauris. p. 188.

[30] Rojava Information Center (2022). The SNA Encyclopedia: A Guide to the Turkish Proxy Militias. pdf

[31] “With factional infighting | Factions accused of looting private and public properties in Afrin.” (2022, October 15). Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. link

[32] Human Rights Watch (2024, February 29). “Everything is by the Power of the Weapon”: Abuses and Impunity in Turkish-Occupied Northern Syria. p. 24. pdf

[33] “Five Years of Injustice are Enough!” Investigative Study on Violations Against Kurds and Yazidis in Northern Syria” (2023, November 13). Syrians for Truth and Justice. link

[34] “After displacing more than 300,000 Kurdish residents of Afrin people, Turkish-backed factions seize more than 75% of olive farms and receive the price of the first season in advance” (2018, September 20). Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. link

[35] Human Rights Watch (2024, February 29). “Everything is by the Power of the Weapon”: Abuses and Impunity in Turkish-Occupied Northern Syria. pdf

[36] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2020, September 18). Syria: Violations and abuses rife in areas under Turkish-affiliated armed groups – Bachelet. link

[37] “Syria: Complaint to Eight UN Special Rapporteurs about Torture in Afrin.” (2023, February 2). Syrians for Truth and Justice. link

[38] Human Rights Watch (2024, February 29). “Everything is by the Power of the Weapon”: Abuses and Impunity in Turkish-Occupied Northern Syria. pdf

[39] “Five Years of Injustice are Enough!” Investigative Study on Violations Against Kurds and Yazidis in Northern Syria” (2023, November 13). Syrians for Truth and Justice. link

[40] Akazawa, T., S. Muhesen, H. Ishida,. O. Kondo & C. Griggo (1999). New Discovery of a Neanderthal Child Burial from the Dederiyeh Cave in Syria. Paléorient, 25(2), 129-142

[41] Schmidinger, T. (2019). The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds: Self-Determination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Afrin Region of Rojava. PM Press. p. 23.

[42] Ibid. p. 25

[43] Ibid. p. 26

[44] Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (2021). Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic.

[45] Nizar al-Hassan (2024, January 30). UNESCO urges end to Turkish violations on Afrin’s archaeological sites. North Press Agency. link

[46] “Afrin – Turkish-backed groups undertake live ammunition exercises in Iron Age temple” (2019, November 11). Syrians for Truth and Justice. link

[47] Schmidinger, T. (2019). The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds: Self-Determination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Afrin Region of Rojava. PM Press. p. 10.

[48] Nouraddin Ahmed (2020, April 26). Turkish forces and opposition groups destroy nine Yazidi shrines in Afrin. North Press Agency. link

[49] Al Shbib, S. (2022). The Building Techniques of Byzantine and Early Islamic Fortifications in Northern Syria: Cyrrhus as a Case Study. In Building between Eastern and Western Mediterranean Lands. BRILL. p. 116. link

[50] Sino, S.M. (2019a). Special Study Documenting Grave Encroachments on Historical Sites in Afrîn by the Turkish State and its Allied “Olive Branch’’ Syrian Factions Between 20/1/2018 and 3/11/2018. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate.

[51] Abdul Massih, J., Benech, C., & Gelin, M. (2009). First results on the city planning of Cyrrhus (Syria). Archéosciences, Supplément (33 (suppl.)), 201–203. https://doi.org/10.4000/archeosciences.1584

[52] Sino, S.M. (2019a). Special Study Documenting Grave Encroachments on Historical Sites in Afrîn by the Turkish State and its Allied “Olive Branch’’ Syrian Factions Between 20/1/2018 and 3/11/2018. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate. p. 27.

[53] Ibid. p. 28.

[54] Ibid. p. 29.

[55] Ibid. p. 31.

[56] Ibid. p. 32.

[57] Sino, S.M. (2019b). Violations of the pyramidal tomb in Syros after the Turkish occupation. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate.

[58] Novák, M. (2012). The Temple of Ain Dārā in the Context of Imperial and Neo-Hittite Architecture and Art. Temple Building and Temple Cult Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.), 41–54.

[59] Ibid. p. 41.

[60] Sino, S.M. (2019a). Special Study Documenting Grave Encroachments on Historical Sites in Afrîn by the Turkish State and its Allied “Olive Branch’’ Syrian Factions Between 20/1/2018 and 3/11/2018. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate. p. 9.

[61] Ibid. p. 10.

[62] Novák, M. (2012). The Temple of Ain Dārā in the Context of Imperial and Neo-Hittite Architecture and Art. Temple Building and Temple Cult Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.), p. 46.

[63] Sino, S.M. (2019c). The Ancient Mound of Ein Dara is once more subject to Turkish depredations. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate. p. 3.

[64] Sino, S.M. (2019a). Special Study Documenting Grave Encroachments on Historical Sites in Afrîn by the Turkish State and its Allied “Olive Branch’’ Syrian Factions Between 20/1/2018 and 3/11/2018. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate. p. 13.

[65] Novák, M. (2012). The Temple of Ain Dārā in the Context of Imperial and Neo-Hittite Architecture and Art. Temple Building and Temple Cult Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.), p. 49.

[66] Sino, S.M. (2019a). Special Study Documenting Grave Encroachments on Historical Sites in Afrîn by the Turkish State and its Allied “Olive Branch’’ Syrian Factions Between 20/1/2018 and 3/11/2018. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate. p. 20.

[67] Sino, S.M. (2019c). The Ancient Mound of Ein Dara is once more subject to Turkish depredations. Report for the Afrîn Antiquities Directorate. p. 4.

[68] بوست [Nedaa’ Syria] (2019, 20 September). “تدريب بالذخيرة الحية لمقاتلين من القوات الخاصة في الجبهة الوطنية للتحرير متخرجين حديثاً ” [Live ammunition training for newly graduated fighters from the Special Forces of the National Liberation Front]. Youtube. video

[69] Thoreau Redcrow. (2023, 28 March). Five Years of Hell and Evil: Turkish Occupied Afrin. The Kurdish Center for Studies. link

Comments are closed.