The Mythical Symbolism of Birds Among the Kurds

By Himdad Mustafa

Birds have long held significant symbolic value in numerous mythologies and cultures throughout history, embodying multifaceted roles that represent a diverse array of themes. These include freedom, spirituality, guidance, protection, transformation, wisdom, creation, and fertility. While the significance of birds varies across different cultures, their symbolic importance remains a prominent and enduring feature within the mythological traditions of many societies, including that of the Kurdish people. This article presents an introduction to the rich symbolism of birds among the Kurds.

First, it is helpful to reflect on the historical observations of outsiders. The French orientalist Thomas Bois observed that Kurds engage in various forms of pantheism, including prayers directed towards birds, horses, and even snow.[1] Russian Kurdologist M. B. Rudenko noted that “according to the beliefs of the Kurds, birds freely communicate with the realm of the afterlife. This is reflected in Kurdish folktales in which birds appear as intermediaries between the living and the dead, as well as harbingers of the imminent death.”[2] O. L. Vilchevskii, while studying the Kurds in Mukriyan, observed that: “magical birds and miraculous lions with supernatural properties are among the most common characters in Kurdish folktales. Among the zoomorphic depictions engraved on tombstones, which are widespread in most regions of Kurdistan, along with horses and sheep, images of lions are also prevalent. Additionally, although less frequently, there are depictions of Leontocephalines and winged lions.”[3] In Kurdish beliefs, as Bois remarked:

“Birds serve as models of virtues and vices, and if one wants to know one’s true friends, those who will always be faithful, it is no use turning to the Starling, the Stork, the Crane, nor even to the Partridge, but to the Magpie, who is no seasonal bird who flies away when bad times come. In all these stories there is often delicately implied a moral, after the manner of La Fontaine.”[4]

During traditional Kurdish marriage ceremonies the bride’s entrance into her new home is accompanied by various rituals, such as crossing a threshold strewn with coins and sweets, or in some cases, the release of a bird. This act is believed to bring good fortune and happiness.[5] Additionally, the Kurds hold various beliefs regarding birds, including the use of their feathers in healing rituals and as symbols of power. Sometimes little holes are made in the grave and filled with water, so that birds and animals may drink to the departed. During the elections of chieftains, it was believed that if a bird alights on a candidate’s head, he is considered to be God’s own choice.[6] The deeply rooted belief in the spiritual power of birds is also reflected in the tradition of releasing birds for the purpose of seeking healing for the sick.[7] Besides the sacred birds, there are also mythical birds like simsiyār, a white bird of prey with black wings which reaches the age of a thousand years.[8]

Birds feature prominently in Kurdish folktales and legends, which are “the favorite genre of Kurds.”[9] These narratives encompass a wide range of stories, including those that realistically depict the societal characteristics of a specific historical period, as well as magical and fantastical tales. Additionally, there are animal tales, often didactic in nature, resembling parables.[10] In the Kurdish folktale of Eagle and Peacock, which addresses the theme of power and survival, it is told that:

“A society of birds gathered to choose their king. Each bird wished to rule. One of the birds, which was more self-assured than others, proud of its beauty, stepped onto the square and, spreading its colorful wings, declared, “I am a beautiful peacock, and since I am more beautiful than all the other birds, I am worthy of becoming the king of all birds.” When the birds saw the peacock, standing alone on the square with its outstretched, multicolored wings that competed with the rays of the sun, they all exclaimed, “Indeed, the peacock is worthy of kingship because of its beauty, and we choose it as our king!” The birds began to congratulate the peacock on its upcoming rule.

At this moment, a turkey came out onto the square and, bowing to the peacock, said, “My king, may I ask your majesty a question?” The peacock spread its wings and said, “Go ahead, ask.” The turkey said, “In our society, it is customary to offer all our wealth and property to the king because the king protects our society and possessions. But if we were attacked by an eagle and a falcon, how would your majesty advise us to defend ourselves?” To this question from the turkey, the peacock remained silent.

Then the birds realized that the peacock’s boasting was useless and its beauty was powerless. Birds needed a strong protector who could defend them both in battle and in times of trouble. Therefore, the birds decided to make a fearless and powerful eagle their king.”[11]

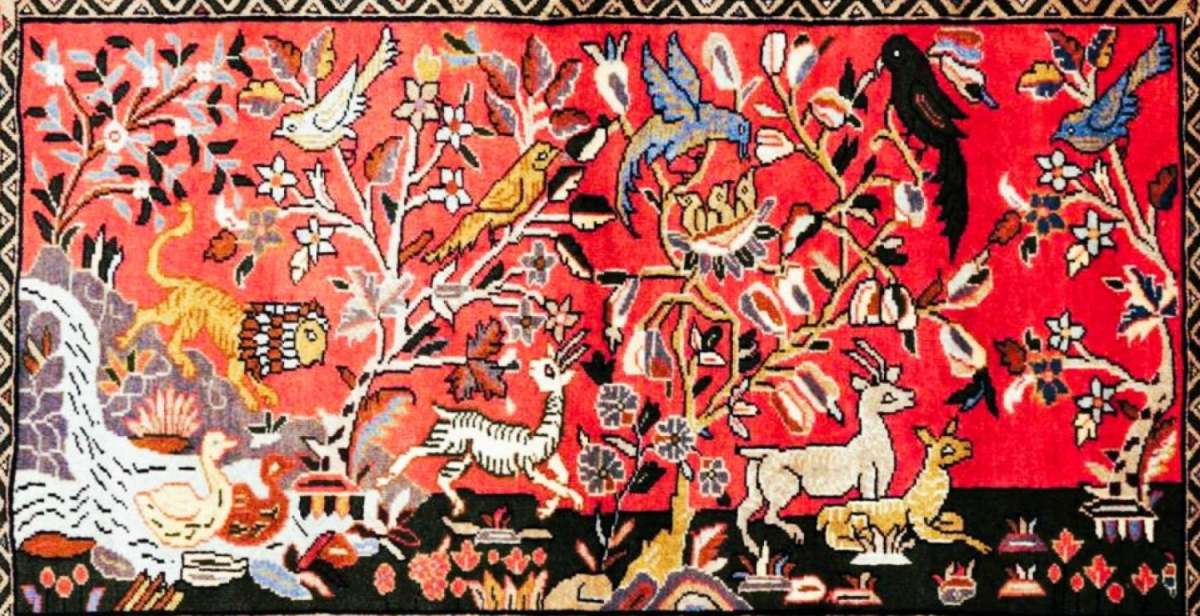

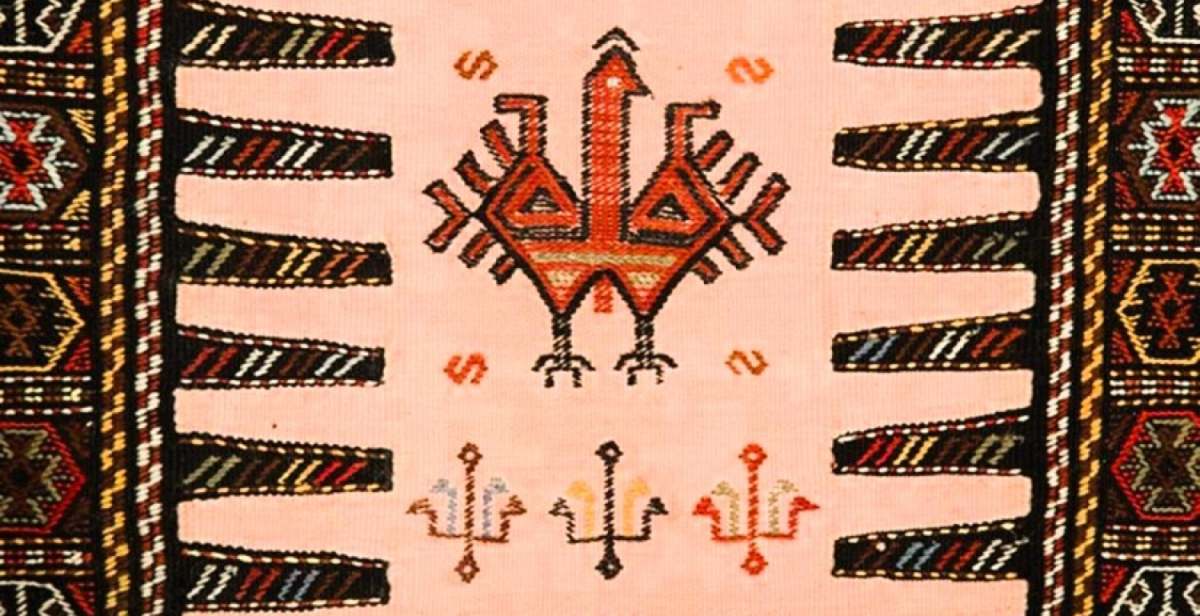

Birds are also richly featured in Kurdish rugs, T. F. Aristova pointed out that “Kurdish carpet designs retain numerous ancient thematic motifs, with elements reflecting the Kurds’ religious beliefs, daily activities like animal husbandry, farming, and craftsmanship, as well as their natural environment. For instance, sun motifs are predominantly found in carpets crafted by Yazidi Kurds, symbolizing the religious beliefs of fire-worshippers from the past. Sun symbols occasionally appear in carpets made by Muslim Kurds, indicating a shared cultural and potentially ancient religious heritage. Symbolic bird figures are also frequent, sometimes depicted realistically and at other times stylized geometrically.”[12]

The Guardian Birds

In the 1880s, French anthropologist Ernest Chantre travelled through Kurdish lands and made the following observation about the cult of birds:

“In every village inhabited by Kurds in Kurdistan and Mesopotamia, there are sacred birds. For instance, in Biredjik, it’s the ibises that grace the region with their presence during spring, from March to June; specifically, the Ulbis commata, typically found in Abyssinia. Near Urfa, storks are the honored residents, while in Sooverek, it’s the crows. In other places, you’ll discover roller birds, starlings, or various passerines nesting in the earthen walls of houses, unless they’re burrowed right into the ground. This reverence for the guardian birds of the village is so serious that a naturalist risks genuine danger in killing even a few samples of these birds, even at a great distance from the villages.”[13]

One of the most widely revered guardian birds among the Kurds is the stork. Peter Lerkh in 1856 recorded that the Kurds consider the stork (leklek in Kurdish) to be a sacred bird. They believe that in harvest time, they travel to Mecca and Medina. When they depart, they are believed to go to some distant place, where they all assemble together in a temple. Here the old ones die, and the young ones alone return to their nests where they were reared.[14] According to Kurdish folk belief, lek means ‘to Thee’; and leklek is taken to mean ‘To Thee praise, to Thee thanks.’[15]

The guardian birds symbolize prosperity and are believed to bring good fortune to the community in which they reside. A traveler through Mukri Kurdistan in 1890 wrote that in the area between Sainkala to Mianduab storks have built their nest “on every available vantage-ground, so that the whole place is alive with these sacred birds—a sure sign of peace and prosperity.”[16] Later, An observer in 1955 wrote that in the regions located to the south of Lake Urmia “The Kurds regard the stork as the harbinger of spring; no one would harm a stork. It is not uncommon to feed these animals, and it even happens that a broken stork leg is skillfully splinted. The storks, in turn, are on friendly terms with the local residents: they walk behind the plowman in the fields and accompany the shepherd to the pasture.”[17]

Birds as Divine Healers

In the Kurdish tale ‘Shaisma’il and Arabi-Zangi,’ a blind hero seeks help under a tree where two doves land. These doves, aware of his situation, suggest a method for him to regain his sight. After one of the doves advises him to use a fallen feather to restore his vision, the hero follows the instructions and successfully regains his sight. This theme of healing through the guidance of doves is echoed in other Kurdish tales such as ‘Ahmad, the Knower of People, Horses, and Weapons.’[18] In ‘The World-Revealing Goblet,’ fairies in the form of birds perched on a tree assist in the resurrection of two individuals.[19]

In another Kurdish tale “Dervish,” a similar situation involving a miraculous feather repeats: three doves resurrect the killed sons of three brothers. To make the feather miraculous, it needs to be dipped in a spring beneath a mountain.[20] In another Kurdish fairy tale, ‘Benger,’ tells the story of a hero who is given a feather by the Padishah ‘king’ of the Birds for feeding the entire flock during a time of famine. The hero spreads out his tablecloth, strikes it with a stick, and all sorts of food appear. The birds flock to the feast and are finally satisfied. They take to the air, and the king of the birds plucks a feather from his wing and says to Benger: “Keep this feather in your pocket. When you are in trouble, call for me, and I will be of service to you.”

Similarly, in the Kurdish tale “Rostam, Son of Zal,” the Sīmurgh bird serves as the protector of Zal’s family hearth. Zal’s wife was unable to bear a child, but Sīmurgh aided in the childbirth and healed a wound with its feather. In the same tale, Sīmurgh helps the hero Orindj, carrying him to the other side of a river, giving him one of its feathers, and promising to come to him every time he strikes it against a stone.[21]

These various tales showcase the recurring theme of the mystical power of feathers, particularly those from magical birds. These feathers act as agents of healing, resurrection, and aid, emphasizing the sacred role of birds in these Kurdish cultural narratives.

The Rooster

The image of a rooster is commonly associated with deities of dawn, the sun, and divine fire across many traditions. Among the Kurds, the white rooster is considered a vigilant symbol, the watcher and caller to prayer,[22] akin to the rituals of Mithraism where a rooster awakens the devout for prayer. In Zoroastrianism, the rooster (known as Parōdarsh) is affiliated with Sraosha, the Yazata (divinity) of obedience. According to the Vendīdād, a book in the Avesta concerned with the battle against demons, during the last part of the night, the time when the fire is most threatened by the powers of darkness, Ātar, the fire god, summons Sraosha for assistance, prompting the faithful to gather wood. Sraosha, in turn, wakens the bird Parōdarsh (“the one who sees forward”) to call for prayer. It is believed that during this duty, Parōdarsh assumes the role of Sraošāvarez, the assistant priest of Sraosha.[23]

The Divine Eagle

In a mysterious Kurdish tale, the zāy tree (‘tree of birth’) and tāy falcon restore the King’s sight, having been obtained from a distant land of fairies beyond Mount Qāf, guarded by demons.[24] The tale is significant for its depiction of the eagle as a powerful and divine creature. Moreover, this tale is probably a mutated remnant of Kurdish creation stories still found in both Yarsani and Yezidi traditions, in which the supreme deity in the form of a bird perches on the Tree of Life.

The Yarsani Kurds particularly venerate the eagle. They believe that God is incarnated in the eagle, and that the King-Eagle, or Shāh-bāz, represents the Divinity as the universal King who has chosen to inhabit the living form of an eagle because this form, with its specific characteristics, is best suited to manifest the theophany and reveal the divine power in a physical appearance. God is also called Shāh-i Shāhbāzān, the king of royal eagles. Theophanies (encounters with a deity) are always associated with a white eagle. Even if someone dares to compare themselves to the manifestation of God to boast about their own power, they are spoken of as a black eagle and not a white one. White was the color reserved for the divine eagle, explained by the purity it symbolises, making it the only suitable color for the Divine.[25]

Mokri pointed out that the symbols of the eagle, the Sīmurgh, and the sun share the common characteristic of evoking sublimity and majesty, attributes naturally associated with God. In various folk tales, a magician displays dominance over others by transforming into an eagle. Ancient pharmacopoeias (medicine catalogues) attribute supernatural powers to the eagle, prescribing the consumption of eagle blood for strength and courage.

Humai

According to Kurdish beliefs, the responsibility of sending rain rests with God, who employs Solomon, the ruler over all animals, as an intermediary. Solomon conveys the order to Humai, a mythical bird akin to the Phoenix. Humai’s task is to gather all the birds and instruct them to collect water from the sea or ocean, dispersing it over the designated area. The size discrepancy among the birds explains the variation in raindrop sizes, while hail and snow are attributed to birds flying too high in the colder regions of the sky.[26]

Additionally, in Kurdish classical poetry, the bird Humai is often portrayed as a symbol of joy and abundance. While Persian mythology associates the shadow or alighting of the Huma bird on a person’s head or shoulder with the prediction of kingship, this particular motif is not known within the Kurdish tradition.

Sīmir, A Bird Deity

Sīmir,[27] also known as Sī, is both a mythical and divine bird in Kurdish lore, often referred to as the ‘king of birds’.[28] It assumes different bird shapes, including the peacock (tāwūs), rooster, eagle, and stork. Sīmir ‘the bird Sī’ is the Kurdish equivalent of the Iranian bird Sēnmurw or Sīmurgh, which takes different shapes in different cultures and the same name was used for real birds and fabulous composites as well as for benevolent and malevolent beasts.[29]

The dual nature of Sīmir in Kurdish beliefs becomes more apparent when it is identified as a tāwūs ‘peacock’. Alexandre Jaba recorded that in Kurdish tāwūs signified the “name of the devil.” He mentions a Kurdish curse in Northern Kurdish, “be tawusé here”, meaning ‘go to the devil (hell)’.[30] In central Kurdish, tawas signifies ‘hell,’ leading to the curse, “wa tūn ū tawas”, meaning ‘go to hell.’[31] Hazhar Mukriyani also mentions another curse in Central Kurdish “tawāsiyāy tawas,” which translates to “to hell with it”[32] Among Yārsāni Kurds the equivalent of this phrase is “wa tūn-ī tawas.”[33] On the other hand, the bird Tāwūs or Sīmir is a divine figure whose meaning signifies God. Among the Yezidis, Melekê Tawûs (Tawûsî Melek) is often called Sīmir when addressed in prayers. Mohammed Mokri noted that among the Yarsanis the name Sīmurgh (Sīmir) is often used to refer to ‘God.’[34]

In Kurdish mythology, the Sīmir or Sīmurgh motif is usually combined with various other stories that do not necessarily have anything to do with it. The hero has been sent, for one reason or another, on a dangerous journey, and he has arrived at an uninhabited place. There he rests under a big tree and sees that a snake or a dragon is just about to eat the young of a big bird. The hero kills the snake and goes to sleep. The bird arrives and sees the hero sleeping. It thinks that this is the enemy who has eaten its young in several previous years, but the young tell the bird that the hero has, on the contrary, saved them. The bird is thankful and promises to do for the hero anything he wishes. The hero has an arduous task to accomplish and he has to get to a faraway place. The difficulties are so great that even the bird exclaims: “Would it be that my young had been devoured this time too? It would be more pleasant to me than helping you to get there!” But because of the solemn vow that the bird has given, it carries the hero to his destination and, in some versions, also gives him a feather that he has to burn at a critical juncture so that the bird can come to help him again.[35]

The motifs found in Kurdish tales are shared with broader Iranian, Mesopotamian, and Jewish traditions. In a tale Sīmir carries the hero out of the netherworld; here she feeds her young with her teats, a trait that agrees with the description of the Sēnmurw by Zādspram. The bird also feeds the hero on the journey while he feeds her with pieces of sheep’s fat and water.[36]A Mesopotamian connection was discussed by Jussi Aro, writing that “in the Kurdish folktales the eagle Sīmurgh helps the hero as in the Mesopotamian Lugalbanda epics and in the Etana myth.”[37] Following Aro, Schmidt maintains that “the correspondence of these [Mespotamian] motifs with the Simorḡ stories in the Šāhnāma and the Kurdish folktales is obvious, showing that they are of common Near Eastern heritage.”[38] Similarly, the scholar of the Ancient Near East Stephanie Dalley maintains that the Kurdish and Persian tales about Sīmurgh bear traces of Mesopotamian tradition: “There are also Kurdish folk-tales in which the Simurgh bird has its young eaten from its nest in a tree by a snake and then becomes the guardian helper of a hero. Like the eagle in the Babylonian myth of Etana, the Simurgh bird in Kurdish stories carries the hero heavenwards on its back.”[39] A connection between the Kurdish tales and the gigantic bird pušqanṣā from Talmudic lore was also discussed by D. E. Gershenson.[40]

Sīmurgh represents the union between the earth and the sky, serving as a mediator and messenger between the two. In Kurdish folklore, the crane (stork) often serves as a mediator, thus replacing Sīmurgh. It can be assumed that such interchangeability was a conscious phenomenon. In the Bundahishn, the crane is mentioned among the birds that fly, like Sēnmurw.[41]

As is well known, the peacock Melekê Tawûs is widely venerated in Kurdish religions. It is the most sacred bird in Yezidism. Irina I. Moskalenko remarked that:

“The world of birds represents the world of celestial spirits in the symbolic universe of the Kurds. The image of the Peacock, sometimes tabooed with the name of death, reflects the transition between life and death, guarded by the guardian of paradise and likely replacing the archangel of light, Gabriel. At the conceptual level of this transition, ancient Iranians had ideas about the judges of human souls, Mithra, and his assistants Rashnu and Sraosha.”[42]

Aristova noted, “The Kurds, especially the Yazidis, associated the image of the bird with their religious object of worship, the peacock Melekê Tawûs. Depictions of Melekê Tawûs on carpets are often not entirely clear. Sometimes, he resembles a crow or a rooster, while other times, he is represented as a stylized bird.”[43] In some Kurdish tales, it is identified as a female figurine and referred to as the Malīka Tāwūs ‘Queen Peacock.’[44] According to a widespread legend about the peacock Melekê Tawûs among Kurds: “this sacred bird was supposed to bring happiness to people. But centuries passed, and the magical bird Malek-Taus did not appear. ‘Some archer shot down the peacock’s wings,’ they said. ‘And the peacock remained somewhere beyond the mountains, beyond the seas.’ Gradually, the Kurds came to the realization that they had to fight for their own happiness.”[45]

In 1879, Friedrich von Hellwald recorded a mourning song among the Sunni Kurds lamenting brutal Turkish oppression, which ends with the following lines:

“Cursed be the one who separates two loving hearts!

Cursed be the murderer who knows no mercy,

The grave will never give up its dead,

Only the curse is heard by Melek Taus (i.e., King Peacock).”[46]

It was customary for Kurds with achievements on the battlefield to wear feathers, particularly those of a peacock. In the 13th century, an Italian traveler noted that Kurds “spot red feathers in their hats signifying power and pride.”[47] A French traveller in 1838 observed that “rewards await those who have distinguished themselves through their bravery after the action. The most glorious of these distinctions is a peacock feather; each enemy killed earns one for the victor. They attach this brilliant trophy to their headwear. Therefore, do not tell a Kurdish rider that his turban is burned by the sun due to a lack of feathers to shade it, as it would be the most injurious insult.”[48] Mokri noted that “in popular tales, the feathers of the Sīmurgh are usually used as warrior ornaments. The hero, adorned in his armor, would add a Sīmurgh feather to his helmet to enhance its brilliance.”[49]

In the early 20th century the American missionary F.M. Stead, mentions the Tāwūs worshipers among the Yarsani/Ali Ilahi Kurds, “One of the branches of the `Ali Ilahi cult, known as the Tausi, or Peacock sect, goes still further afield, and venerates the devil. While these people do not actually worship Satan, they fear and placate him, and nobody in their presence ventures to say anything disrespectful of his Satanic majesty (…) There are three principal divisions of the `Ali Ilahi sect, viz., the Davudi, the Tausi and the Nosairi.” Stead explains the name of Tâwûsî by relating the well-known tradition that the Peacock was the guardian of Paradise, who let Satan in so that he could seduce Adam and Eve.[50] In a Yarsani text which narrates various cosmological myths, when the Day of Resurrection arrived, the jinns turned to their king, Malak Tâ’us and said, ‘O King, it is clear that the Day of Resurrection has arrived.’ Malak Tâ’us looked into the box of trust, saw that the Day of Resurrection had arrived and said to Mostafâ, ‘take me to the King of Love.’[51]

John Verzeau (1656-1735), the head of the Syrian Missions in the city of Saida in Aleppo, in 1699, documented a distinct group of Syrian Kurds, which was separate from the Yezidis, “They also have dealings with the devil. In the past months, some of them came to Saida with a cage containing the devil in the form of a bird, from which they learned about future events.”[52] Although he does not mention the name of the sect nor of the bird idol, it is evident it was Tāwūs (either rooster or peacock) due to its association with the devil. Samuel Clarke in 1689 reported that in the northern parts of Syria, “there dwell the Cardi, or Coerdes, a People who pay Veneration to the Devil, and the slender excuse they allege for it is, to prevent his doing them Mischief, they being on the contrary assured, that God being in his Nature good, he will not injure them.”[53] The sect was probably the Kurdish sun-worshippers, known in Arabic as Shamsiyya who were found in Upper Syria and Kurdistan until the 19th century. Italian traveler Abbé Giovanni Mariti who toured through Syria in the 1760s, in a section titled ‘Of the Kurds’ writes that the Syrian Kurds follow three religions (Di tre religioni sono i Curdi di Soria), and that there are Muslim Kurds (Curdi Maomettani), Yezidi Kurds (Curdi Iasidi), and Shamsiya Kurds (Curdi Sciamsi). Of the last sect he wrote they hold “the same belief and worship as the Iasidis.”[54] He further describes the sect as follows:

“Their first worship consisted principally in adoring the sun; which, in their idea, was the sole creator of the universe. They inclined themselves before his earliest rays, and retired when he set; carefully avoiding the approach of night, which they said was the empire of the demon. Such of the Kurdes as have preserved this religion of their ancestors are called Chamsis, or Solarins.”[55]

In many cultures, the peacock represents the solar symbol. In Iran, there is a metaphorical name of the Sun – Tāvus-e Falak (‘The Peacock of Heaven’). In Ancient Egypt, the peacock was considered a symbol of Heliopolis, the city where a temple of the Sun was located. Similarly, in Ancient Greece, the peacock was also regarded as a symbol of the Sun. Melekê Tawûs is associated with solar beginnings. Depicting Melekê Tawûs as a peacock aligns with the solar symbolism attributed to this bird in other mythologies, including that of early Christians.[56]

Certain Kurdish groups worshipped represented in the form of a rooster, as the Christian missionary H. J. Van-Lennep reported in 1875, “there are still more distinct remains of the ancient idolatry, which is now practiced in secret, because involving all participants in the penalty of death. Such are the peculiar rites of the Yezidies and of the heathen Koords.” He observed that among the Yezidis “when they speak of the devil they do so with reverence, as Melek Taoos (King Peacock,) or Melek el Koot (the mighty angel).” As for “the heathen Koords”, he wrote “There are also other tribes who hold to this same Melek Taoos, but they are not ‘worshipers of the devil,’ nor do they believe in Parsee dualism…They appear to believe in a sort of Pantheism, and the transmigration of souls… We have known a woman from among these people who was converted to Christianity and baptized… We understood from her that the Melek Taoos was there set up and worshiped; that a cock was killed as a sacrifice to it; that wine was drunk in abundance by all present… The accompanying illustration [shown below on the left] is a faithful copy of one of the curious images worshiped both by the Koords and the Yezidies, which play so important a part in this ancient and almost effete superstition. It is made of brass, rudely carved, and has never before, we believe, been given to the public.”[57]

This Kurdish group was almost certainly the Tirahiya Kurds, mentioned by Ethel Drower,[58] and Woolnough Empson, who visited Kurdistan in the 1910s and wrote that “Yazid, a deity of the Tarhoya tribe of the Kurds, who are not devil-worshippers, is supposed to be identified with the worship of trees.”[59]

Of contemporary note, current-day Yezidis are pushing back against this harmful and oft-repeated false stereotype of them being “devil worshippers”, as such ignorance was used by ISIS to justify their genocide and enslavement in 2014.

In Summary

In exploring the historical sources as well as the beliefs and folklore surrounding sacred birds, three distinct types could be identified. The first category entails a revered bird treated as a deity, referred to as Sīmir or Tāwūs, often depicted as either a peacock or a rooster. The second category consists of mythical birds. The third category comprises real sacred birds that receive special forms of worship, adoration, or veneration not typically extended to ordinary birds.

These sacred birds are regarded as symbols of guidance and protection and are believed to possess protective and auspicious qualities for the communities they inhabit. Their mythical symbolism provides insight into the profound spiritual heritage of Kurdish culture, highlighting the cultural reverence for birds as sources of solace and divine assistance in times of need. For this reason, birds should be seen as important cultural symbols of the Kurds, equal in significance among the Kurdish mythological pantheon to the sun and trees.

References:

- Bois, T. (1966). The Kurds. Beirut: Khayats. pp. 118-119. ↑

- Rudenko, M. B. (1982). Kurdskaia obriadovaia poeziia: pokhoronnye prichitaniia. Moskva: Nauka. s. 39. ↑

- Vilchevskii, O. L. (1961). Kurdy: vvedenie v etnicheskuyu istoriyu kurderskogo naroda. Moskva: Nauka. s. 156, n.18. ↑

- Bois, op. cit., p. 117. ↑

- ibid, p. 51. ↑

- Ibid, pp. 34, 82. ↑

- Mokri, M. (1967). Le Chasseur de Dieu et le mythe du Roi-Aigle (Dawra-y Dāmyāri). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p.28. ↑

- Justi, F. (1878), Les noms d’animaux en Kurde. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. p.22 ↑

- I.V. Bazilenko (ed.), The Kurds: Legend of the East (in Russian), s.43-44. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Translation by Z. A. Yusuloyeva, in I.V. Bazilenko (ed.), op. cit.,, s.43-44. ↑

- Aristova, T. F. (1958). “Poyezdka k Kurdam Zakavkaz’ ya” (A Visit to the Kurds of Transcaucasia), Sovetskaya Etnografiya, No. 6. Cf. “The Kurds of Transcaucasia,” Central Asian Review, Vol.7, 1959, pp.169-170. ↑

- Chantre, E. (182). Aperçu sur les caractères ethniques des Anshariés et des Kurdes, Publications de la Société Linnéenne de Lyon (1-2). pp. 165-185 (especially p.175). ↑

- Lerkh, P. (1856). Issledovaniya ob iranskikh kurdakh i ikh predkakh, severnykh khaldeyakh, vol.I, s.16.Clark, W. (1864). “The Kurdish Tribes of Western Asia,” New Englander and Yale Review 23, p. 46. ↑

- Douglas, W. O. (1958). West of the Indus. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. p.41. ↑

- Bent, J. T. (1890). Azerbeijan, Scottish Geographical Magazine, 6 (2). pp. 84-93 (p.92) ↑

- Plattner, F. (1955). Die Verbreitung des Weißstorchs im Gebiet des Urmiasees (Iran) – Vogelwarte – Zeitschrift für Vogelkunde 18. pp. 178 – 179. ↑

- Rudenko, M. B. (1970). Kurdskie narodnye skazki. Moskva: Nauka. Dzhalil, O., et. el. (1989). Kurdskie skazki, legendy ipredaniia. Moskva: Nauka, 1989. ↑

- Tofiq, M. H., Thackston, W., transl. (2005). “Kurdish Folktales.” Reprinted from The International Journal of Kurdish Studies 13(2), p. 37. ↑

- Dzhalil, op. cit., s. 271. ↑

- Rudenko, ibid. ↑

- Clark, W. (1864). “The Kurdish Tribes of Western Asia,” New Englander and Yale Review 23, p. 46. ↑

- Grenet, F. & Minardi, M.. (2021). The Image of the Zoroastrian God Srōsh: New Elements. Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 27. 154-173. ↑

- Tofiq, M. H., op. cit., pp.51-57. ↑

- Mokri, op. cit., pp. 32, 40. ↑

- Bois, op. cit., pp.101-102. Nikitin, V. P. (1956). Les Kurdes. Étude sociologique et historique. (Paris: Klincksieck. ↑

- Prym, E., A. Socin (1887). Kurdische Sammlungen, Erzählungen und Lieder in den Dialekten des Tūr ‘Abdin. St. Petersburg, p.56. Ritter, H. (1968). Kurmānci-Texte aus dem Ṭūr’abdîn. I. Kärboran. Oriens, 21/22, 1–135; Trever, C. V. (1938). The Dog-Bird. Senmurw-Paskudj, Leningrad, 20-21. Schmidt, H. (2002), Simorḡ. EIr online. ↑

- Prym, E., ibid. ↑

- Schmidt, H. ibid. ↑

- Jaba, A. (1879). Dictionnaire kurde-français. St. – Pétersbourg: l’Académie Impériale des Sciences. p.274. ↑

- Ferheng.Info, link ↑

- Mukriyani, H. (1990), Henbane Borîne. ↑

- Rezaie, Iraj (2019). Locating the Ancient Toponym of “Kindāu”: The Recognition of an Indo-European God in the Assyrian Inscriptions of the Seventh Century BC. Iran, 58:2, 180–189. ↑

- Mokri, op. cit., 69, n.92. ↑

- Aro, J. (1976). “Anzu and Simurgh.” In: B. L. Eichler, J. W. Heimerdinger and Å. Sjöberg (eds.). Kramer Anniversary Volume. Cuneiform Studies in Honor of Samuel Noah Kramer. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 25. Kevelaer: Butzon and Bercker, Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 25-28, esp. p. 27 ↑

- Schmidt, ibid, ↑

- Aro, op. cit., 25-28. ↑

- Schmidt, ibid, ↑

- Dalley, S. (1998). “The Sassanid Persia and Early Islam,” in Dalley, S. (ed.), The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 173. ↑

- Gershenson, D. E. (1994). “Understanding Puškansa”, Acta Orientalia 55, 23–36. ↑

- Zaporozhchenko A. V. , Cheremisin D. V. (1997). Arimaspy i Grify: izobrazitelnaya traditsiya i indoyevropeyskiye paralleli, Vestnik drevneĭ istorii, No. 1, 1997, s.83-90. ↑

- Moskalenko, I. I. (2018). Traditsionnoe soznanie indoiranskikh narodov v ego kulturno-istoricheskom razvitii: monografiya, s.160 ↑

- Aristova, T. F. (1966), Kurdy Zakavkaz’ya: istoriko‐etnograficheskiy ocherk, s.74 ↑

- Mackenzie, D. N. (1962). Kurdish dialect studies, vol.2, p.125. ↑

- Aziya i Afrika segodnya, №. 4-12, 1961, s.9. ↑

- Hellwald, F. v. (1879). Die heutige Türkei, bd. 2. Leipzig: Otto Spamer. 197-198. ↑

- Borbone, P. G., ed. (2020). History of Mar Yahballaha and Rabban Sauma. (Hamburg: Verlag Tredition,). ↑

- Bélanger, Ch. (1838), Voyage aux Indes-orientales, par le nord de l’Europe, les provinces du Caucase, la Géorgie, l’Arménie et la Perse, t.ii. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. 242. ↑

- Mokri, p.33. ↑

- Bruinessen, M. v. (2014). Veneration of Satan Among The Ahl-e Haqq of The Guran Region, Fritillaria Kurdica, № 3, 4. 20-21. ↑

- Ibid, p.24. ↑

- Camillo Beccari, ed. (1914), “P. Ioannes Verzeau S. I. ad p. Ioannem M. Baldigiani S. I. Saidae, 31 aug. 1699,” Relationes et epistolae variorum, 1697-1708, vol.13, p.89-91, esp.91. ↑

- Clarke, S. (1689). A New Description of the World. London: Hen. Rhodes. pp.111-112. ↑

- Mariti, A. G. (1769). Viaggi per l’isola di Cipro e per la Soria e Palestina fatti da Giovanni Mariti fiorentino dall’anno 1760 al 1768, t.2. pp. 43-45. ↑

- Mariti, A. (1792). Travels Through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine; with a General History of the Levant, Vol. 1. Dublin: P. Byrne. p.260; Mariti, A. (1793) “Of the Kurdes of Syria”, The Sentimental and Masonic Magazine, vol. 3, pp. 512-517, esp. p.513. ↑

- Omarkhali, Kh. (2006). “Symbolism of birds in Yezidism“, World Congress of Kurdish Studies, organized by the Kurdish Institute of Paris in partnership with Salahadin University, Erbil, Kurdistan Region in Iraq. ↑

- Van-Lennep, H. J. (1875). Bible Lands: Their Modern Customs and Manners Illustrative of Scripture London: John Murray. 709-710. ↑

- Stevens, E. S., later Drower, E.S. (1923). By Tigris and Euphrates. London: Hurst & Blackett. p.198. ↑

- Empson, R.H.W. (1928). The Cult of the Peacock Angel: A Short Account of the Yezidi Tribes of Kurdistan. H.F. & G. Witherby: London. p. 178. ↑

Comments are closed.