The Euphrates, the Jazira, the symbolism of myth, and the conflict in Syria

By Aqil Said Mahfouz

In a story by Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano titled “The River of Oblivion,” he says: “The Roman legionnaires stopped on the bank of the river. They never crossed it, because whoever crosses the River of Forgetting and reaches the other side forgets who they are and where they came from” (Galeano, The Book of Embraces). Despite its age, this myth provides a symbolic framework for understanding aspects of the dynamics of remembering and forgetting, conflict and resolution, death and life in Syria.

Perhaps the story recounts, or intensifies, an oral experience regarding the fate of those who drink from the river or attempt to cross it. It instills fear and terror at the very thought of drinking from the river, let alone crossing to the other side. Consequently, it establishes a single barrier between memory and oblivion, existence and non-existence, the ego and the other. But what the river truly causes is not just forgetting, but liberation from the burden of memory that defines us and thereby identifies our enemies, to borrow Carl Schmitt’s definition of the essence of politics.

Isn’t forgetting here also a false, dreamy, or illusory promise of peace—a peace that can only be achieved for the other by relinquishing their identity?

Two Different Worlds

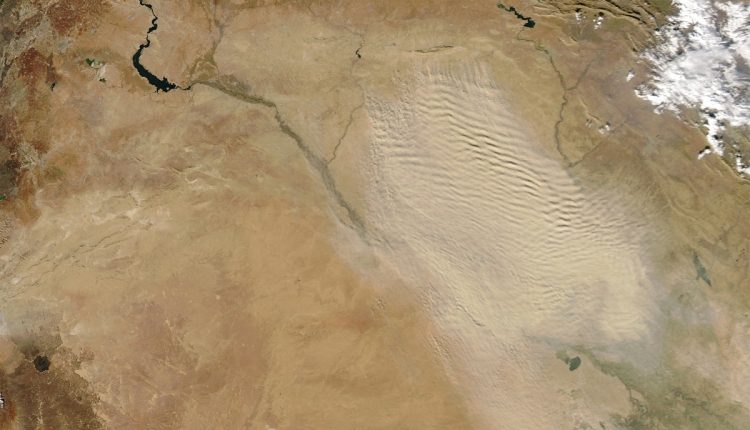

The first thing that comes to mind when reading the story is the Euphrates River and the Jazira region, along with the symbolic connotations that intertwine with the tale or myth. The ‘Euphrates Line’ was one of the earliest dividing lines on the maps of the conflict in Syria. On both sides of it, different patterns of meaning, power, and interaction emerged. Additionally, there were various checkpoints, control points, flags, banners, and alliances. Sometimes, patrols from several countries (Russia, the US, Turkey, etc.), as well as local flags, would meet in the same place, with minimal friction and clashes, but with much suspicion and apprehension. Over time, this line has come to symbolize two different worlds—and, of course, two different horizons. This symbolism is renewed, reinforced, and perhaps even eternalized—explicitly or implicitly—in the language of eternity that dominates this beautiful Levantine landscape. (See Table 1).

| Symbolism | In Greek Mythology | In the Syrian Context |

| Function | Separation of the living from the dead; forgetting one’s identity after crossing. | Marginalization of the periphery by the center; forced forgetting of cultural identity. |

| Results | Liberation from the burden of memory. | Suppression of diversity, weakening of identity claims, and reinforcement of centralized dominance. |

| Political Interpretation | – | A tool for denying reality and justifying economic and security neglect of diverse regions. |

Table 1: Symbolism of the River of Oblivion in Greek Mythology and the Syrian Context

Internal Colonization

Paradoxically, the successive authorities in Syria, since the formation of the modern state after the end of World War I, have treated the Jazira region as if it were a colony. It represents both an opportunity and a threat: an opportunity as a major source of resources and rents (economic gains and resources), and a threat because it is a site of local identity, territorial claims, self-management, or aspirations for fair and balanced participation in resources, politics, and power. The Jazira region has taken on a special status, closer to annexation than integration. It appears neglected in terms of development, yet it remains significant in terms of economic rents and, of course, security.

This paradox aligns with what can be called the Lacanian paradox (after Jacques Lacan, the French psychoanalyst and thinker): the region is not truly forgotten. It is fully remembered as a black hole in the existential map of the “center” historically; a “point of non-existence” whose resources are to be absorbed rather than integrated as a full presence. Isn’t this economic oblivion the ultimate form of hostile political remembrance? Indeed, this dynamic can be traced through the perspective of political, intellectual, and social actors in Syria since the early 20th century.

It is a relationship of a plundering, hegemonic center and a plundered, subordinate periphery. This dynamic can be traced back to the late Ottoman period, when the region was part of the Aleppo Vilayet, with some areas belonging to other provinces that are now in Iraq and Turkey, and parts functioning as an independent administrative unit (a müffariyah, such as the Deir Ezzor müffariyah). This administrative distribution laid the groundwork for later complexities of identity and allegiance. Historically, the region has been a source of grain and livestock, occupying an important position along the Silk Road and serving as a vital commercial hub between northern Syria, Iraq, and Anatolia.

After the formation of the modern state in the Middle East following World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the colonial mentality re-emerged, but in its most primitive forms: demographic changes, selective census practices, education, and services. These policies reflected an effort to weaken any autonomous aspirations in the region, relegating them to the periphery of political decision-making, governance, and the dominant value systems within the country.

Kurds, Syriacs, Assyrians, Armenians, and others speak of the heavy impact of state policies, which inflicted significant neglect, exclusion, and abandonment upon them, leading to large-scale population migrations abroad. Overall, the region has become a paradigmatic space of denial: a resource-rich geographical area with a declining population. From this perspective, its inhabitants—who hold existential or identity-based aspirations—are seen as a threat to the ‘central state’ and to a number of increasingly influential regional and international actors operating within the country.

The special status of the Jazira region, in the eyes of the state center historically, has led the latter to:

- ‘Open the doors’ to a pattern of participation and resource distribution, but again, only to the extent that it contains any tendencies toward self-awareness or dissent. This is reinforced by a unifying, inclusive ideology, security institutions, dependency networks, and a complex clientele.

- ‘Close the doors’ to equal citizenship and participation, regulate interactions between the various ethnic, religious, tribal, and clan components, suppress or weaken political and party expressions, and so on. (See Table 2).

| Criterion | State Centre (Damascus) | Periphery (Jazira region) |

| Policies | Centralized governance, unifying ideology. | Development neglect, political exclusion, security control. |

| Resources | Exhaustion of peripheral resources (oil, gas, agriculture). | Deprivation of local resource revenues, economic marginalization. |

| Identity | Imposed mono-identity. | Ethnic and religious diversity (Kurds, Arabs, Syriacs, Assyrians, etc.), attempts to suppress local identities. |

| Dealing with demands | Accusations of ‘separatism’ or ‘external dependence’. | Historical demands for autonomy or federalism, suppressed by force or marginalization. |

Table (2): Comparison between the “Centre” (Damascus) and the “Periphery” (Jazira region) in Syria

Negative Perceptions

Many people are unaware of the true nature of the region, including those in power. However, a significant number label it as ‘separatist,’ often attributing this label primarily to the Kurds, as they are the most active and self-aware component, and the most eager to shape a distinct identity and entity there. These perceptions reflect some aspects of the broader conflict dynamics and the challenges of reaching consensus. This does not diminish the awareness, dynamism, and aspirations of other components.

The paradox here is that the centre remembers the accusations and perceived threats, yet it forgets the underlying causes, objective conditions, and the subjective (and third-party) stakes involved in the region. But is the centre truly forgetting, or is it merely pretending to forget? This so-called forgetfulness is not a failure of memory but an act of forced amnesia. It is an ideological process to ‘remember’ the Jazira as an existential threat requiring repression, rather than as a partner. This forgetting is essential for maintaining the centre’s logic, which depends on denying the reality of the region.

Here are some of the deeper reasons behind negative perceptions of the region:

- The region has a relatively broad socio-ethnic spectrum: it comprises various religions, sects, ethnicities, and cultures (Arabs, Kurds, Syriacs, Turkmen, Circassians, among others), with varying proportions. Additionally, there is religious and sectarian diversity within each group, including Sunni and Shia Muslims, Alawites, and Christians belonging to different churches.

Resources and Historical Aspirations

- The region possesses abundant resources, especially oil and gas, including major fields such as: Rmelan (northeast of Hasaka, which produced around 100,000 barrels per day before 2011), Suwaydiyah (south of Rmelan, which produced approximately 60,000 barrels per day), and Jabsa. There are also other fields like Al-Ward and Al-Omar, as well as gas fields and agricultural crops such as wheat, cotton, and barley. (Note: The figures are approximate and provided to clarify the main point of the text. They are not intended for detailed economic analysis or documentation. The reader may encounter various estimates with differing figures.)

- The region has historically aspired to establish an ‘entity’ or ‘self-administration’ within a federal or decentralized Syrian state since the 1930s. This underscores that these demands are not a recent phenomenon arising from the current crisis. The project was close to realization but was thwarted by international circumstances and other factors that prompted France to withdraw from Syria. Additionally, internal conditions aimed to abort the idea of an independent identity or autonomy that Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, and others had been working toward. These factors have repeatedly influenced the region throughout its history.

- When resources, ethnic and cultural diversity, and social and political vitality combine, they generate a growing social momentum that could shift the balance of meaning and power within the country and the region. This dynamic has historically shaped the policies of central authorities toward the Jazira region, whether during the Ottoman era, the Mandate period, or the post-Mandate Syrian state. The centres appeared preoccupied with questions such as: How can they contain what is perceived as a threat in the Jazira? And, as frequently discussed, how can they extract the region’s resources without fair distribution or balanced allocation? For several decades, the region has ranked low on government spending priorities.

Reproduction

Currently, the same visions and perceptions are being reproduced almost identically, with a more explicit presence of the ‘external’ influence—whether near or distant—which rejects the existence of a special case in the region. This external influence works tirelessly to place the region in a state of perpetual threat, destabilize security and stability, wage complex wars—both material and symbolic—and do everything possible to narrow the opportunities for a safe and stable life. For many in the region, conditions of life are better, but concerns about the future persist.

This is the dynamic behind the region’s peripheral and marginal status relative to the ‘centre,’ which itself is considered a ‘periphery’ relative to a ‘centre’ or ‘centres’ within the region and globally.

Additionally, there is increased pressure and accusations of separatism and foreign interference, with the region being blamed for all the repercussions of economic and political failures in the centre, particularly after 2011. This reflects a continuity of policies that have been in place for decades, inherited and perpetuated by successive regimes.

The Dynamics of Remembering-Forgetting

The dynamic of remembering-forgetting is a political act and one of the most important mechanisms of interaction between the ‘centre’ in Damascus and the ‘periphery’ in the Jazira region. As previously mentioned, the centre ‘remembers’ that the region is one of resources and threats, and ‘forgets’ the factors that drive it (the region) to demand decentralization, participation, and equitable distribution of material and moral resources. However, forgetting extends beyond that. The centre believes that forgetting—represented by abandonment, neglect, and efforts to erase identity and cultural memory—may lead people to forget their identity and preoccupy themselves with seeking the lowest possible level of existence and basic needs.

This is where the centre falls into its cynical trap: it seeks to impose oblivion as a tool of control, but forgets that the attempt to erase memory is itself a violent act of remembrance that more radically reproduces the repressed identity. The more the centre tries to bury this identity, the deeper it buries the seed of rebellion within the soil.

An Alternative Model?

Building or restoring collective memory at the national and regional levels is not a singular act, nor can it be entirely centered around ethnicity, nationality, religion, or sect. It is everyone’s business and everyone’s responsibility. The fundamental goal is to create a space where all components can coexist safely. The greatest challenge facing the country is: How can Syrian society be based on ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity? And how can a Syrian state be founded on pluralism and decentralization?

There are undoubtedly theoretical answers and hypothetical scenarios, sometimes rhetorical or rhetorical in nature. However, it remains difficult to identify broad consensus on these answers, and then translate rhetoric or conceptual frameworks into concrete action. Merely mentioning pluralism and decentralization continues to evoke perceptions of threat among a large segment of political actors. Discussions of pluralism and decentralization are often laden with meanings that contradict their essence, especially in the context of ongoing social divisions, sharp polarizations, and violence.

The Five Rivers

Let’s leave Galeano’s interpretation of the river, or rather our previous reading of Galeano’s account of it. Instead, we examine the original myth of the “River of Oblivion,” as found in Greek and Roman mythology. The river is one of the five rivers of the kingdom of Hades in the underworld. These rivers form the boundary between the land of the living and the land of the dead. They are: the River of Hatred and Eternal Oath (Styx), the River of Sorrow and Pain (Acheron), the River of Forgetfulness (Lethe), which is most closely related to the theme of this text, the Blazing Fire (Phlegethon), a symbol of torment, and the River of Lamentation and Howling (Cocytus).

While the Lethe River symbolizes natural individual oblivion in mythology, in the Syrian context, oblivion is a systematic, coercive act used as a political tool to suppress diversity. It represents a form of escape and evasion from the demands of resolution, and may symbolize denial of reality, abandonment of a territory whose response might cause unmanageable headaches, or perhaps more.

| The River | Original Symbolism | Application to Syria |

| Lethe (Oblivion) | Forgetting memories. | The policy of forced forgetting of local identities and denial of diversity. |

| Styx (Hatred) | Eternal oath and hostility. | Escalation of sectarian rhetoric and hatred between the periphery and the centre. |

| Acheron (Pain) | Sorrow and suffering. | The suffering of the region’s inhabitants due to neglect, displacement, and oppression. |

| Phlegethon (Fire) | Torment and purification by fire. | Ongoing wars and violence used as tools of control. |

| Cocytus (Lamentation) | Mourning over the ruins. | Destruction of infrastructure and cultural heritage, turning the region into a perpetual conflict zone. |

Table (3): The Rivers of the Underworld and Their Symbolic Applications to the Syrian Conflict.

In conclusion, the symbolic aspects of all the rivers mentioned—not just the River of Forgetting—may apply to the case of the Euphrates as a symbol of this fertile Levant, and more specifically as a symbol of the rift between eastern and western Syria. If this rift remains unresolved and continues without efforts toward reconciliation, the Euphrates might transform from being merely a river of forgetting and abandonment (with negative and hostile remembrance of the region at its core) into a river of hatred (Styx), grief and pain (Akheron), blazing fire and war (Phlegethon), and lamentation, mourning, and standing amidst ruins (Kokytos). So far, the Euphrates deserves to be associated with these attributes and symbolisms, or at least is on the horizon of nearly all of them. Essentially, the Euphrates is not just a single river; it is a multifaceted one—more than just a symbol of division. It is a space, in the Gijekian sense (referring to the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek), where oblivion meets hatred in a desperate attempt to create order, while reality persists in chaos of meanings. The question is not: Do we forget? But rather: What do we forget to live, and what do we remember to fight for? The real question is: How can the river of forgetting be transformed into a bridge for communication and coexistence?

References and Sources

- Eduardo Galeano, The Book of Embraces, translated by Osama Esber (Damascus: Dar al-Tali’a al-Jadida, 2015).

- Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, translated by Sumer al-Mir Mahmoud (Cairo: Madarat for Research and Publishing, 2018).

- Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, translated by Uday Jouni (Baghdad: Fawasal for Publishing and Distribution, 2024).

Comments are closed.