Weaponizing Wildfires: Deforestation as Dekurdification

By Dr. Thoreau Redcrow

Burning down forests so you can build castles upon the ashes sounds like an ancient moral parable about the pitfalls of rapaciousness, not a modern occupation strategy by the second largest military in NATO.

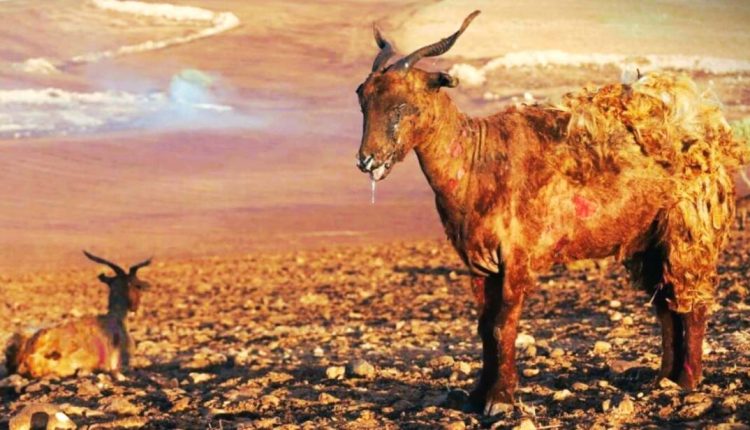

The recent massive wildfires that ravaged Northern Kurdistan / Bakur (southeast Turkey) between Amed and Mêrdîn killed 15 people and left 78 injured. Beyond the human toll, over 1,000 sheep and goats were also burned to death, with 200 more being treated for severe burns. With temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F) in the preceding weeks, shrubs were tinder-dry, creating ideal conditions for the raging inferno to scorch nearly 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) of farmland, residential areas, and forests.

However, while on the surface these fires appear to be “acts of nature” (or God, for believers), a look at the history of Turkey’s military occupation of Kurdish areas and the structural ways the Turkish state systematically aims to drive Kurds away from their ancestral lands, shows that such fires are often one of the most effective weapons at Ankara’s disposal.

The ways that Turkey deploys supposed “wildfires” against the Kurds are emblematic of the wider ways that the 20+ million Kurds in Bakur face subjugation under a state that does not view them as befallen fellow citizens who require assistance, but as a disloyal un-Turkish nuisance who deserves cruelty. In this calculation, Turkey sees every ‘natural’ tragedy (earthquake, wildfire, flood, landslide, drought, etc.) in Kurdish areas as a potential opportunity to harness Mother Nature as an ideal weapon, since it gives them plausible deniability. In these cases, it is not the Turkish military who literally murders Kurdish civilians—as they often have with their notorious JİTEM death squads—but an imperceptible force which Ankara can claim is beyond their control.

Yet, when one digs deeper on nearly all of these natural tragedies, you see a Turkish state that either directly caused the disaster, crafted the conditions for it to occur in the first place, or neglected to come to the aid of Kurds once it began—thereby maximizing the damage. For example, the latter case is evident when looking back on the large earthquakes which struck the Kurdish majority areas around Licê (1975), Çewlik (2003), and Wan (2011), killing 2,300, 177, and 600 people (mostly Kurds), respectively. In fact, during those instances, Turkey preferred to send Turkish soldiers to repress the anger over there being no government aid, rather than the aid itself.

And like with earthquakes, when it comes to forest fires, such tragedies should not be viewed as unfortunate calamities, but rather manufactured and weaponized anti-Kurdish ‘pogroms’, concealed in the cloak of a natural disaster. As a result, understanding the ways this dehumanizing social engineering process typically occurs is instructive for understanding what it means to be an occupied Kurd within Turkey.

Culpability for the Latest Inferno

The technical cause for the recent fires were faulty electricity poles and cables that were improperly maintained by the private Turkish electric company DEDAŞ. The company is notorious for neglecting Kurdish areas and price-gouging Kurds without any accountability. In the most recent incident, the company also quickly replaced all the poles the day after the fire to conceal any evidence of their culpability. But while the conditions for the fire were aided by negligence, the human tragedy of the fires was exacerbated by abandonment, due to the Turkish state refusing to provide assistance to curtail the fires once they began.

Melis Tantan, Kurdish spokeswoman for the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy (DEM) Party’s Ecology and Agriculture Commission, denounced Ankara’s delayed response to the fire, declaring:

“It is not acceptable that a night vision helicopter was not sent to the region from the moment the fire started. The fire spread to a large area in a short time. And unfortunately, the calls were silenced. In such cases, early intervention from the air can prevent the fire from spreading to large areas. Unfortunately, our country is constantly caught unprepared for such disasters. This is not a coincidence or fate. This is a case of those responsible not fulfilling their responsibilities.”

As anger amongst Kurds grew towards Erdoğan’s spiteful regime for not assisting with the fires, Turkish firefighters carried out a disingenuous display of assistance, with one helicopter needlessly dropping water from the Göksu Dam on hay bales after the fire was already extinguished. Local Kurds responded to the sham aid by shouting, “Film this disgrace of a helicopter!”

Across the border in Rojava, Kongra Star representatives Nisreen Rajab and Shilan Khalil from the Şêx Meqsûd neighborhood of Aleppo also criticized Turkey’s response, remarking:

“The policies of the occupying state are based on exclusion and the national dimension, as two days ago it repeated the scenario of indifference to the lives of the Kurds, as happened during the earthquake that struck the region last year, in a crime under which the Turkish occupation state violates the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The ideal solution to secure the future of the Kurdish people in all parts of Kurdistan, especially Bakur Kurdistan, is to implement the democratic nation project.”

Fire as a Counter-Insurgency Tool

Eliminating forests and trees as cover for armed guerrillas is a traditional counter-insurgency tactic for occupying militaries battling an indigenous resistance movement. From the British Military in the 1950s using herbicides in Malaysia, to the United States Army dropping Agent Orange on the dense jungles of Vietnam, the rationale is that any vegetation provides visual sanctuary for those opposing you, especially from air attacks. In the case of Turkish forces in Northern Kurdistan, it is no different; however, they have historically decided to proverbially ‘kill two birds with one stone’, both destroying the forests and the Kurdish villages located beside them.

During the 1990’s, as the Turkish military burned down over 4,000 Kurdish villages, they also deployed wildfires as a sinister tool to prevent defensive forest ambushes from Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) guerrillas who were resisting them. And because the best way to decipher the truth about the Turkish state is to view their accusations as confessions, Ankara has even accused PKK guerrillas of burning down their own forests they live in—preposterous propaganda that Erdoğan’s personal ‘media’ stenographers are happy to regurgitate.

This phenomenon of wildfires as a form of counterinsurgency against the Kurdish resistance has been researched by several academics. For example, in an analysis of how the Turkish government set forest fires around Dersim in 1994 to force Kurds to evacuate the area and curtail Kurdish guerrillas, Pinar Dinc, Lina Eklund, Aiman Shahpurwala, et al. produced an article titled ‘Fighting Insurgency, Ruining the Environment: the Case of Forest Fires in the Dersim Province of Turkey’ (2021), which examined if there was a correlation between the number of forest fires from 2015–2018 and Turkish military operations against the PKK. What they found was that statistical analysis suggested a significant relationship between fires and conflicts around Dersim, showing that as the number of conflicts increased or decreased, the number of fires generally followed.

“The state sets the forest on fire every other year, they don’t let the trees grow. As soon as the trees are as tall as a human being, they set another fire.”

— Resident of Dersim, from the 2021 research

Other findings from the aforementioned research were that local Dersim residents linked the Turkish state to the fires, which they accused of setting directly through military exercises or refusing to extinguish when they spontaneously erupted. Local testimonies often highlighted how fires began after Turkish soldiers fired howitzers or explosives from police stations and dropped bombs from combat helicopters. Informants in the area added that forest fires typically occurred around Turkish kalekols (military strongholds situated on top of hills), believing that they were set to give security officers a clearer view of the surrounding area. A report from the Centre for Dersim Studies soon confirmed this perception by concluding that the majority of forest fires in the area were the result of airstrikes and attacks launched from Turkish military strongholds. Another common opinion cited by the local community was that Turkey had long been aiming to bring about demographic change in Dersim, by driving local Kurds away from their homes to open the area for mining and energy companies.

An earlier research article and study conducted by Joost Jongerden, Hugo de Vos, and Jacob van Etten titled ‘Forest Burning as Counterinsurgency in Turkish-Kurdistan: An analysis from space’ (2007), also investigated Turkey’s weaponization of forest fires from 1990 to 2006 against the Kurdish resistance movement. In that study, satellite images were utilized to evaluate the claims of intentional forest burning for village destruction and then cross referenced with geo-data from eyewitness accounts. What that study discovered was that in 1994 alone, 7.5% of the total forest in Dersim and 26.6% of the forests near villages (within a 1.2 km radius) were burned. Ultimately, the analysis concluded that: “The more severe burning around destroyed and evacuated villages is important evidence for the intentionality behind the use of fire against civilian populations and underscores the claim of human rights abuse.” The study also found that there was a high frequency of fires in cases of village destruction (85%), suggesting that destroying such Kurdish villages, “almost always went hand in hand with burning of forests, orchards and fields around it.”

But, perhaps, when it comes to understanding the role that forest fires have played around Dersim, it is helpful to look at the words of Kurdish political prisoner Selahattin Demirtaş, who in 2021 from Edirne Prison tied such infernos back to the 1938 Dersim Genocide, professing:

“The reason for not putting out the forest fires in Dersim is not inefficacy. Most of the forests in that region are burned consciously and no one is allowed to intervene. This is a conscious and official policy that has been in effect for decades. Everyone knows this truth, but no one unfortunately dares to say it. Forests are burned on the same grounds Dersim was bombed in 1938.”

This would help explain why Mustafa Karasu, of the Kurdistan Communities Union’s (KCK) Executive Council, reminded Kurds after the latest fire that, “To ask for something from the state that wants to commit genocide against you is to ask for something from your executioner.”

Replacing Trees with Castles

In September of 2020, Anil Olcan conducted an interview with environmental historian Dr. Zozan Pehlivan, where she noted that the Kurds living near Mount Judi (Çiyayê Cûdî) referred to the annual fires as “implementations” (uygulama), an accusatory term implying an operation that is intentionally applied under a certain strategy and rationale.

According to the World Forest Fires Database, between 2003 and 2016, fires in that region of Bakur were most frequent during the area’s harvest season, between July and September. But, whereas such fires traditionally lasted 3–4 days, they now lasted up to 20, leaving a scorched path of ecological destruction and destroyed livelihoods for locals who relied on the forests to survive. Location-wise, the forest fires were concentrated in two primary Kurdish regions: the eastern portion of the Amed-Êlih-Bidlîs triangle and the corridor connecting Sêrt, Colemêrg, and Şirnex.

Curiously, these two regions were also the location for widespread Turkish military lookout towers and fortifications, that were ‘coincidentally’ built throughout the area prior to the breakout of large fires, and would ‘conveniently’ then clear out their sightlines and widen their field of vision. Professor Pehlivan described this process, observing how:

“In the last two decades, an incredible number of guardhouses, or as they call them locally, ‘castle-stations’ (kalekol), have been built in areas where forest fires are most intense. These castle-stations are built on dominant hills like medieval fortified citadels, with the forest areas around them radically trimmed. On top of that, the forests and plateaus around the castle-stations were declared high security zones and closed to civilian access.”

With these castled areas now closed to civilians, when forest fires did break out, locals were barred from entering to help extinguish the blaze on “security” grounds, meaning they would often consume everything in their wake. The result was cleared out barren hill tops, with Turkish military outposts overlooking the newly scorched wasteland.

Cutting to Sell Instead

Alongside forest fires, cutting down the trees is another way that the Turkish state loots and exploits Northern Kurdistan. One of the areas where this takes place is near Şirnex, where Turkish soldiers are currently using village guards to cut down the trees, after local Kurds refused to do so. In recent months, thousands of trees have been cut down and loaded onto trucks to be transported and sold in other cities. This follows the pattern of November 2023, near Şirnex’s Gabar Mountain, where after the forests were chopped down, a series of Turkish military watchtowers, roadworks, and oil exploration sites took their place. A few months prior, in August 2023, thousands of trees were also cut down in a rural area near Çewlik, so that the Turkish military could construct a new military base.

In the case around Şirnex, reports from the ground are that everyday dozens of trucks and lorries filled with cut trees head for Riha and Antep. Apparently, the Turkish military overseeing the deforestation, which began in 2021, told the village guards that the process of cutting down all the trees would take ten years in total.

According to Agit Özdemir, from the Mesopotamia Ecology Movement, Şirnex “is a laboratory for the state”, where they are cutting down 500-year-old memorial trees. Which is similar to how jihadists in Turkish occupied Afrin continue to cut down the sacred ribbon trees of Yazidis in that region. But not only that, rather than cutting from the bottom as is typically done, in Şirnex they are digging the roots out of the ground so that trees will never regrow in that area again. According to Özdemir, “The destruction is at such a level that there is no return”, with him adding:

“The goal of this deforestation is dehumanization. In the 1990s, we used to see this during village evacuations: ‘Dry the water, let the fish die.’ Today, this strategy continues with variations. Not only the guerrillas, but the [Kurdish] people as a whole are seen as enemies.”

Killing the Living Forest’s Soul

When the Turkish state intentionally starts or refuses to extinguish naturally occurring wildfires in Kurdish areas, their motivations can be multi-faceted. There are the strategic military objectives of turning dense forests, which could conceal Kurdistan’s guerrilla defenders, into barren hills with military outposts on all the high points, which then operate as “no-go” security zones. There are economic objectives to remove the rural Kurdish villagers from the area so that for-profit businesses affiliated with the ruling regime can seize those lands and use them to construct urban housing, develop mine excavations, or conduct oil exploration.

There are also the Turkish ultranationalist objectives of wanting to eradicate Kurdishness and culturally assimilate Kurds living in the region, which is easier to do if you uproot them from their ancestral lands and force them into the coastal cities of western Turkey, where they can be exploited as textile workers and not have enough time or energy to preserve their culture. But one of the deeper objectives and motivations exists on the spiritual and metaphysical level, where the Turkish state wants to eradicate the forests because of the deep religious meaning that many Kurds attribute to them and the animals that call those trees home.

Returning back to the translated reflections of Zozan Pehlivan, in her interview she observes how Kurds are affected economically by the forest fires, outlining how:

“When a forest is in flames, it is not the only thing that burns. There are lives tied to that forest. Locals put beehives in the forest, and they collect firewood to keep warm. In late spring and summer, they prune fresh oaks and collect bundles of branches. After the bundles are stacked, they are tightly covered so as to not dry out in the heat of summer. During the winter, oak leaves are a source of nutrition for animals. They are called ‘velg’ in Zazakî, a dialect of Kurdish. The remaining dry branches are used for cooking and heating. They are called ‘percin.’ The forest is an important source of energy for the people in the region. In addition, areas where fires break out are lands with pastures. Good highland grass is harvested in spring to feed the animals during the next winter, while animals graze the remaining grass, which is too short to scythe. When these areas are set on fire, it wreaks havoc on stockbreeding, which is one of the most important sources of income for villagers.”

However, Pehlivan then addresses that deeper cultural and spiritual element, tying it to the Turkification process in wider Anatolia, where Ankara wants people to forget who they truly are, commenting:

“People develop relationships of belonging with their lands, their trees, flowers, animals, and water, which is emotional as much as economic. When someone loses this relationship, they lose the things that make them who they are. The aim behind the village evacuations of the 1990s was to disrupt the relation the people in this place had developed with their culture and language. It is much harder to disrupt this relationship when people remain in their homes/native lands.”

This is especially true from my experience in Kurdish Alevi (Rêya Heqî) areas, whose beliefs are rooted in nature veneration and share far more in common with Yarsanism, Yazidism, or Zoroastrianism than the prevailing Hanafi Islam of the Turkish state. In this way, it is not a coincidence that these Alevi (often Zazaki-speaking) Kurds consider water and trees to be holy, while the regime in Ankara directly builds dams and deforests in their ancestral sacred areas. Turkey is essentially conducting a ‘spiritual assault’ on what gives these Kurds meaning in life, in the hopes that if they can break them on a soul-ular level, they will be less likely to resist on a political one.

In this equation, by burning down the forests, the Turkish state eliminates the ability to have livestock, both because a lack of milk and meat will decrease the community’s physical energy, but also because if certain mountain goats are seen as mythical beings, what better way to shatter the psyche of a people you want to occupy than to cause them psychological trauma by forcing them to watch them all burn—just like they did their grandparent’s Kurdish village in the 1990s?

Comments are closed.