Roundtable: On Rushdi Anwar’s Kurdistan Art Exhibit

By Dr. Hawzhin Azeez

At the Table with Rushdi Anwar

Rushdi Anwar (b.1971-) is a Kurdish artist from Halabja, Kurdistan whose upcoming exhibition, in collaboration with Artes Mundi and the British Council, will be presented at the National Museum Cardiff, UK. A round table was held by Artes Mundi with Dr. Omar Kholeif, Professor Shahram Khosravi, and Dr. Hawzhin Azeez to discuss the upcoming exhibition, which focuses on a number of events and tragedies, including the 1988 Halabja genocide by the Saddam regime during the infamous Anfal campaign and the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Introducing Rushdi

Rushdi earned his Ph.D. in Art from RMIT University, Melbourne, and is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Rushdi’s work draws on his experiences as a Kurd, surviving the chemical bombardment under the Saddam regime during the Anfal genocide, his displacement from Kurdistan, and working and living in the diaspora. His upcoming exhibition uses installations, sculpture, painting, photography, and archival material to present an emotionally vivid exhibition that narrates the Kurdish experience of colonization, oppression, genocide, and trauma. He aims to generate discussions around the plight of the stateless, the displaced, those discriminated against and persecuted as a result of the Sykes-Picot agreement, and the tragedies that continue to unfold as a result for the Kurds.

Rushdi has held solo and group exhibitions in Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Cuba, Finland, France, Japan, Kurdistan, Norway, South Korea, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the USA, and Vietnam.

Rushdi opened the panel discussion by presenting an overview of the main features of his upcoming exhibition, which includes photographs taken during and after the Halabja bombardment, which had been enhanced for further effect with soot and was accompanied by a poem by the renowned Kurdish poet Sherko Bekas. Rushdi stated that “The former Iraqi regime Saddam Hussein attacked my hometown. More than 5,000 people were victims. And more than 10,000 people later on were injured and died in the hospitals. This work is to respond to that after Halabja with the poetry of Kurdish poet.”

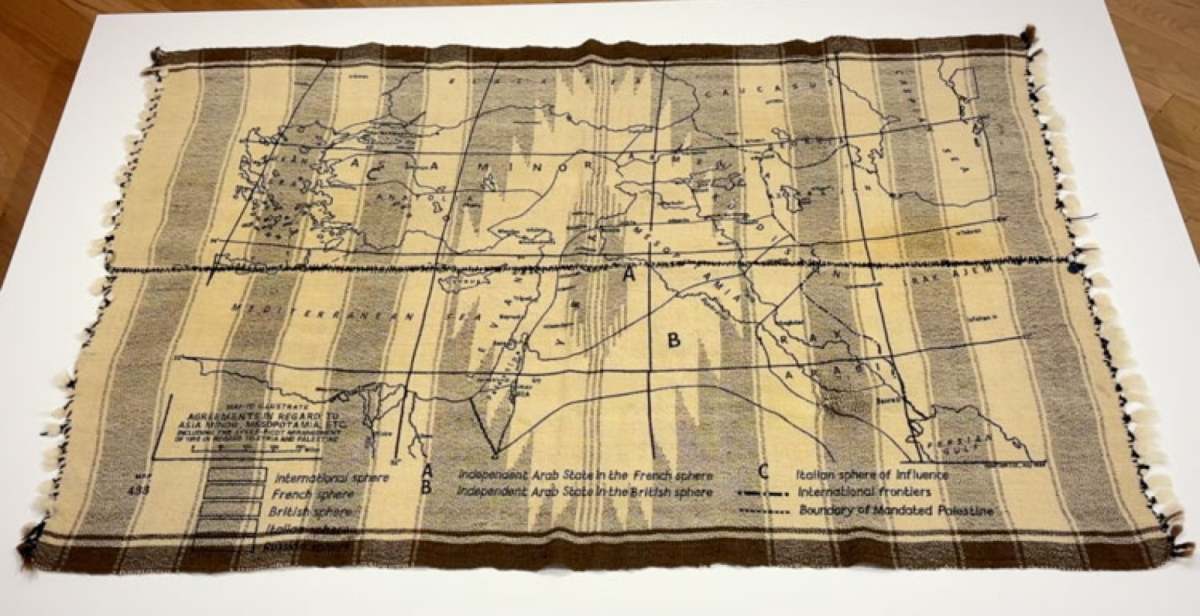

Another aspect of the exhibition includes large side-by-side photographs of Mark Sykes and George Picot, the architects of the division of the Kurds across Iran, Iraq, and Syria in 1916. Their photographs have maps of the Kurdish regions imposed on them. For Rushdi, this part of the exhibition is “looking at basically the hypocrisy of politician and politics, and looking at the repetitive violence in the region, and especially in Kurdistan and Iraq.”

The following is a transcription of the round table discussion that was held via Zoom on Thursday, December 7th. The transcription has been edited by the author to reduce disconnect and increase flow and consistency.

The Roundtable

Dr. Omar Kholeif: I am a curator and author, and I have the privilege to write about Rushdi’s work in the Artes Mundi catalog, which was a continuation of a conversation or dialogue that, I suppose, was begun in a place called Saharsa in the UAE, where we first met, and also where I work…

I was very moved by the [exhibition] in particular, the way that you reanimate historical narratives of trauma through very material means to present a kind of affecting space for feeling. For different kinds of feelings to be felt, whether it’s the materiality of a picture that has been altered by soot, and whether it is these artifacts that are found in these boxes in these cases on these plinths that are using petroleum-like materials to burn and turn them into a form to resemble a form of salvage. But also to notice the evocative patterns on these boxes, which allude to a history that is shared by many different individuals in and around the world.

One thing, and I think this is a question for both yourself and the panel, I suppose, we both struggle with, and I certainly think it requires problematizing, and the return to the question of the term Middle East, as we know, it’s a term that is predominantly used to, or was popularized at least as a military term that links together countries with myriad different ethnic, social, religious, and cultural backgrounds into a supposed entity or whole. Your work in the National Museum of Wales polemicizes that. What do you and the panel think we might offer in terms of a different kind of language or vocabulary in relation to this language, or this term ‘Middle East’ to be, and enable us to be more specific, which is to say the words Kurdistan, or South Kurdistan, or North Kurdistan for example, which is something your work is about. It’s about the resuscitation in the public consciousness of a Kurdish narrative.

Rushdi Anwar: Yes. Absolutely. That’s a very good question. You are right. And the term Middle East, as you mention as a term, has been useful, and the region in that context, you mention. I think now, with the terms, it has been used often, and recently, or a few years ago, it started being here with west Asia, which some people refer to as west Asia, and where most is not Middle East but west Asia. I think this is a proper term that tends to be used. As we know, this part of the world, geographically, is part of Asia. And as I think geographically, it’s correct if you say west Asia. But coming to your question about Kurdistan, I absolutely agree with you. So the terms of Kurdistan, going back to modern history, and with the establishment of the nation-state in west Asia, the Kurds are left out and divided. So among the four new states, which are Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran, we are struggling for identity. For Kurds, in my opinion, there’s no Kurd who does not have a crisis of identity. We have always had this crisis.

It’s because something happened 100 years ago, and we are still paying for it. The new generation is still paying for it. Wherever we go, we have to explain, and if I introduce myself to a little group of people in a simple thing at a dinner table when they ask me where I come from? So I have to give a five-minute explanation of where I come from. And that’s not just me doing so, every single Kurd has this problem. Sometimes it becomes super-complicated and now I am living in South Asia, in Thailand. For this part of the world, they aren’t aware of what is happening in Middle Eastern history, and politics in west Asia which is Kurdistan. Sometimes, I just say, Look, let’s enjoy the dinner. Forget about this. Imagine, you cannot explain where you come from (Laughter’s).

So I struggle for something that was created by the colonial powers more than a 100 years ago, and I was not there. And I’m still paying the price for it. That’s the struggle we are facing. Then, yet we have so many different names for use, and we have Kurdistan, and South Kurdistan, and Western Kurdistan, North Kurdistan, or Bashur, and the different dialects in the Kurdish language. So we have these different terms that are used. To make it simple and easy, when I say I come from Kurdistan and south of Kurdistan, I have to then add, Iraqi Kurdistan, or Kurdistan of Iraq. In order for people to locate me, where I was born or come from, and that my culture is part of this. That’s a kind of struggle that we are facing in my opinion and we are suffering for it.

Omar Kholeif: Would one of the other panelists like to say something?

Hawzhin Azeez: Hello everybody. I’m Dr. Hawzhin Azeez. I am the Co-Director at the Kurdish Center for Studies. I have a lot of thoughts about what Rushdi said, and I will come back to what Dr. Omar said, and the question. First of all, I think what Rushdi has presented is so incredibly powerful and so incredibly necessary, and it is so urgent to have these discussions. You know, Rushdi discussed the bombardments by Saddam, which happened in 1988 and it may seem like it was 30 years ago, but the events and the situation, the humanitarian crisis, and the impact of authoritarian regimes such as Saddam’s and that of repressed minorities are a universal experience for many stateless minority groups, as we are seeing in the crisis that’s occurring.

To combine what Rushdi said with answering Dr. Omar’s question, I think his presentation and the powerful images he has presented will be the collection of different aspects of Kurdish identity, and presents the lost and silenced voice of an oppressed minority within the Middle East. At the same time, this idea of the Middle East of Asia and of Sykes-Picot, and these borders are colonial constructs. It’s up to the people, the oppressed, to define, re-refine, challenge, and determine who they are. Kurdish identity has never been static. It’s always in a state of evolution and change. Like you know, the experiences of many, many other minorities as well.

So what I’m getting from Rushdi’s wonderful exhibition and the beautiful images is two aspects: the necessity and urgency of oppressed and silenced minorities to say I exist and I am Kurdish, and presenting his Kurdishness. But at the same time, what he has presented is so deeply common and universal that you can take the experience of the bombardments and the Sykes-Picot image. You can take the militarized images, and they might not know Sykes-Picot specifically, but you can take them anywhere else and take the photographs with the soot and the emotional photographs, and take them anywhere else and apply them to any other war-torn society, and take it to Syria, Gaza, and several different places and you wouldn’t know it was Kurdish. Because the experiences of colonized minorities across the globe now are so horrendous and yet so similar and common that, as minorities, we connect to them on a deep level.

Shahram Khosravi: I am a Professor in Social Anthropology. I want to start with my colleagues, you know, who started talking about colonization, and for me, colonization always starts with language. I think in a catalog Dr Omar wrote about Rushdi’s work, and he asked the question, What would it mean to live in a place without language? I was thinking of another question posed by American indigenous poet Natalie Diaz, and she asked this question. What is the language unique to life now? I think this is very much about this conversation we have and the art exhibition we are talking about.

I would ask, you know, this question, and what, I mean, we are talking about Kurdish people, and I want to ask this question. What would it mean to live in a place with a language which is against you? You know, which is a language of nation states yes? And Farsi, and Arabic, and Turkish, which has been not only, you know not for Kurdish people. Also, language has been against Kurdish people. So, I think you know, the reaction we have seen through art by Rushdi is exactly this. What does it mean to live with a language which is against you? How we can create art, and reclaim life, and how we can stay alive as a people with this language which is against us. How can we create a new language? How we can create, so I think this language is very important.

Also you know, going back to what Rushdi talked about, and borders, you know, as he shows, it is not people crossing borders, and this is very good example but he is showing the borders crossing people. How borders have crossed Kurdish people in so many different ways, and still, doing that yes? What is the result of that, and its division, and partitioning other people? Not calling them the people, and calling them minorities, and calling them ethnic minorities, calling them tribes. Yes? Tribes is very much still used as a colonial label by not only by the states, but also by anthropologists.

I think I want to finish my intervention by saying that what is important and what I like in Rushdi’s you know, work is a resistance against this division, and how we can create connections through art, yes? Connection, and when we say, resist being called tribes, and say we share the same history of indigenousness, it means that other lands have been stolen from us. It means our breath has been stolen from us. It means that over time, it has been stolen from us, and our language has been stolen from us. I think the power of his art is that.

Omar Kholeif: Before you respond, Rushdi, I wanted to just comment on Dr. Hawzhin Azeez and Professor Shahram’s point about language and the mechanistic tool to communicate. Who bears or holds the responsibility of constructing that language? Now here we are, and I think it’s important to emphasize that we are in a virtual room with British Sign Language interpreters, which until I hosted an event that involved two individuals who were hearing impaired, one American schooled in the ASL American Sign Language, and another in the British Sign Language, and I’m interested that there are dissonances and differences that would be challenging. I thought this very kind of example is really potent because it’s about individuals who could pass for or exist in society, or seem similarly abled but actually do not or similarly quote unquote disabled, but actually do not speak the same language because of where it is that they were schooled, raised, or taught, or by whom. So, the interesting thing about this question and why I asked the question in that text about a world without a language is if we ask, referring to the quote by Natalie Diaz, What is the language that we need now?

The question then becomes: how do those who cultivate that language share that language so everybody has access to those tools, so that there’s a sense of kinship and a sense of belonging that can be ascribed or assessed by certain forms of language? One of the things that I have often done when talking or speaking with Rushdi is that we go back to historical antecedents, and we talk about Andalucía, and we talk about the construction of certain imaginaries, where co-existence which even as a term is polemical, seemed possible. So, I wanted to just say that it’s not enough to invent or remove a term or a language. We need to create. Art is incredibly potent. It speaks to form, material, space, architecture, and design, ultimately leading us to one thing: the effective possibilities that different people can have by using a language of aesthetics. But how do we take that language of aesthetics that Rushdi presents to us and embody a sense of being in the world that I don’t have the answer for?

Rushdi Anwar: For me, language is a mode of communicating, a kind of voice or narrative. For the Kurdish language, a number of bans and limitations exist in its expression by the people. So many Kurdish people have been banned from speaking the language, or even naming their kids, speaking in their own house in the Kurdish language. So they are not allowed to do that. So, but, for me, I think to look at in a bigger different voice of the language, and in response to Professor Shahram is the language of the region, and how we communicate, what’s the new language, and for me, the way I see it.

This language has been for 100 years the language of violence, the language of instability, the language of racism, the language of taking advantage of each other, and the language of punishment, and it doesn’t work. So we have to refine this language, and you have to find the new meaning and how we can communicate with each other. I think, for me, that language is about co-existence. We have to come to a conclusion, and this doesn’t work any more, so until when we treat each other in the region with this language of hate, and that creates a barrier, and segregation, and you are this and that, and therefore I can’t do that to you.

So, I think it’s a time to think about this, to co-exist, and be tolerant towards each other. Once we reach that point, we find the tone of the language, and whatever language we speak in, and physically, and we came to a language to live together, because it’s a reality, and geographically, and a reality, we cannot go anywhere, and as Professor Shahram mentioned, we are the indigenous people of this place. We cannot go anywhere! This became a reality, and with our neighbors, they live with us, and we are part of this. So, this violence and the stability is the answer, and as a language, and of course not. What’s the language, and what’s the solution and conclusion, and how to tolerate and accept each other, create a dialogue, and overcome the difficulties we have been facing for 100 years? How do I reconcile and find a solution? I think that’s a kind of language I believe, even in my art practice, and I am looking forward to representing the difficult facts of artifacts or archival history, or representing these difficult political situations, events or aftermaths, and the genocide of the Kurds.

Through the aesthetic, materiality, and poetry, I try to indicate and say, “Let’s find a new way to communicate. Let’s find a platform, and maybe it’s not just my art practice, and I believe all artists dealing with the difficult issues, and so culture people, and it’s their duty to create a platform for the difficult issues, to represent them, and how to overcome this, and use the culture, and art as a platform to create the dialogue, and debate, and discuss if the culture, because unfortunately, in my understanding and my experience, the politician never will do that. They don’t like to do so.

They use and create a platform for winning elections, gaining power, or doing whatever they want to do with the political agenda. So I think the role of culture is absolutely me as an artist and a part of the culture, and my role is my duty to create a platform through my artwork, and to redefine that language, and it’s not working less fine, and new language, and how to deal with each other. I think that’s my response to the language. Also, it’s about the common experience of the language and the collective experience. So, we focus more about what is we have more in common, rather than to look at what we have more in differences, and to hate each other. By hate, we all know, we don’t go anywhere. Just we go, and we see it, and we just destroy the civilization in the whole region, which is extremely devastating for all humanity, and not just for us. Our history and our civilization have been destroyed throughout history because of the language and difficulties in communicating with each other.

Omar Kholeif: I was wondering if, to follow on from that, one of the terms that was mentioned was this idea of minorities and how we refer to people as minorities not only in art history, and historical context of representing a specific minority ethnic position, and also in a global political arena, which, of course, is something that is deeply problematic because I often say the notaries who sanctioned so-called histories who exist in Western Europe, and in North America, are speaking from a very specific context, but if we look at the Afro-Asian context, as a whole, we are talking about what we increasingly refer to as the global majority, right? Actually, it’s not that we are minorities; it’s that we are a majority, but that within the spaces of minorities, there are delineations and distinct lived experiences and forms of historical erasure that don’t make it out into the world and that are not archived or indexed. It’s about giving and creating a kind of visuality and your work creates a lexicon which is felt from returning to these places. Do other guests have thoughts about the idea of how we create visual space for the very different constellations of people who live in this broad sweep that is the global majority as it’s referred to increasingly?

Hawzhin Azeez: I think there’s an image that Rushdi showed to us from the exhibition, which is the one with the Sykes-Picot. The image of the two generals or diplomats. On the floor, there’s a large prayer mat. To me as a Kurdish woman and as an academic, that mat has a map of the Middle East juxtaposed on it. It’s one of the most powerful aspects of what Rushdi has been saying, and well as the overall tone of the discussion about coloniality, borders, and the silence, and breathlessness that were mentioned. You know, speechlessness. This is so incredibly powerful. I think that his exhibition shows the dangers of colonialism and the nation-states, and it’s also fitting nationalism can itself become the language of an oppressed group. It can in turn become a form of oppression and reproduction of oppression.

Art is basically universal, and it transcends borders, and boundaries, and Rushdi’s art is really showing that, and it’s showing the dangers of nation-states, the dangers of colonialism, and when borders are forcibly imposed. The alternative for Rushdi is you know through his art is a movement towards humanization, and towards the commonality of our common experiences of our humanity of trying to find common grounds beyond these violent colonial borders. Also these colonial borders, and the discussion around language, and the discussion around borders is a very patriarchal process. It’s one that is imposed top-down on to oppressed communities and groups and minorities. One that feminizes these minorities, and that process of patriarchal violence is reproduced on different levels and layers, down into particular communities. This is powerful, and has permeated, and symbolizes the view he is intend to go present.

The overall tone, Dr. Omar you mention in the visual lexicon is powerful. There’s a danger, and there’s also a necessity, and the duality and approach from the perspective of the oppressed to present our pain and suffering, the bombardments, and the black soot and black and white images. And the 12 suitcase-like exhibition, which is very stark, and it’s very cold, almost as if you are standing, you know, at the border somewhere, and you are only your suitcase and your identity to be exposed to the opposing people on the other side there, with Rushdi mentioned with many people who were exposed to the bombardments and forced to flee to Iran, and forced to flee to Europe or to Iran and they have to seek medical treatments. There’s a danger of fetishizing the pain of the oppressed through the process as well. This may as the minorities are very wary of, and very wary of saying we have suffered. On the other side is the discussion of resilience, and you are so empowered, and you are so brave! But, the discussion of minorities and states, forcing borders, and the artificiality of it all, forces us to become different people, and we would be if these discussions of power, hierarchies, oppressions, and the intense violence in the Middle East.

Shahram Khosravi: The masculinity feature of bordering practices. It’s very important also, and you know, brings in this, you know, going back to what Rushdir talked about, and the common language, and what we see, and in the recent, you know, “movement from Rojava and the aim is not going back to ethnic roots. The aim is not to create another nation-state. The aim is to go beyond this colonial thinking, and this is exactly what Frantz Fanon wrote about 60 years ago. What he did, he rejected going back to the roots and that particular identity. No, the aim is to reject and refuse colonial mentality and to create a new humanity. We can create and share together.

This is going back to the piece of art by Rushdi, and showing this prayer mat. If I remember, all the generations grandmother, grandfathers, and sitting, and prayed and they prayed for peace. That work, for me, signifies hope, and I think this is what we are talking about. Hope. A radical hope means how can we keep hope and maintain hope when there’s no hope? Exactly in this moment, we are witnessing this historical moment, and we see the language of dehumanization and what is happening in Gaza. The language of ruination. How we can keep hope. To echo that, radical hope is, you know, not so wholly abstraction. It is really about taking a position within this framework, and I would echo those words as well. I believe that we need radical hope to move us forward, and Rushdi I am curious about your thoughts?

Rushdi Anwar: I felt hopelessness as a teenager who experienced the horrors of Halabja and the deep sense of hopelessness that settled on his psyche, but he went on to argue that in time “I realized there’s always hope, to overcome those difficulties, and always there because, as we discussed about the resilient, and the people and Kurdish people, and most of the people and all the ethnicities, and other nations in the Middle East, the difficulties we go through, and unfortunately the difficult issues we talked about. We always hoped for better, and we look for it. It’s a part of our culture, and we look for a better life and we look for better future. How can we not repeat the same mistakes of the past? How do we eliminate that? I think we have to be hopeful; otherwise, we cannot do anything, to be honest. And, in my own experience, hope gets me to here, and to make art, if I were hopeless, I would not make art at all, since I was a teenager.”

Omar Kholeif: I wanted to note for those listening that we have a few minutes for questions. If you have a question, please pop it into the Q&A box. We will do our best to answer one or two of those. Just to add to that, one of the great things about art as a historical vessel that has a very specific set of formal aesthetic qualities is that it has allowed you to speak across very different social spaces, right? So you can be showing in Germany, you can be showing in the EU, and you can be showing here. And in some senses, one of the great powers of art is that when art is speaking to each other, it can speak on its own terms. That awkward scene at the dinner table of having to describe who you are and where you are from almost doesn’t have to occur.

There’s a kind of innate sense that all art objects are somehow diasporic in a sense as they move into developing new contexts. I believe that’s another great power of creating physical objects that speak to that history and then creating and animating different kinds of iconographic affiliation in the spaces that they move, especially, for example, as mentioned with the Sykes-Picot reference as well. Just as we are sitting here in all these different time zones and able to convene, is it that we feel that the space of art is pulling us together? What else can we do to evolve? I suppose the fundamental issue of language, feeling, and awareness around the issues surrounding gender, sexuality, and representation in these spaces and formal spaces in which we are being constructed. I ask all of you this?

Shahram Khosravi: Going back to hope, it’s not an emotion we have or do not have. Hope is what we do. This is what Kurdish people have been doing—resisting and doing something—by writing poetry. Making and creating art. You know, or doing this. So this hope is practice, you know. I think this is exactly what we are doing here, yes? We are practicing hope. Yes. Another thing I want to say in relation to this is the power of imagination. Politics is about the battle of your imagination, yes? So this is where politicians want to control our imagination, and we refuse. We resist. So imagination is here, and how we can imagine otherwise, and I think again, language and art becomes very you know, central here. Because, my field, social sciences, is not so powerful there. So, I am more for poetic thinking and more for radical thinking, which I find more in art and poetry than, you know, the social sciences.

Hawzhin Azeez: Building on what Professor Rushdi said, hope is a practice; it’s action. It’s doing something, and I think what we have seen speaking of Kurdish people, and the way that Rushdi mentions that politics is patriarchal and politicians are making these violent decisions to divide and create a dumpster fire for lack of a better term in the Middle East which we are seeing vividly at the moment. I think that you know the Kurdish slogan, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Women, Life Freedom) and a Kurdish woman’s struggle for freedom we saw combust into life in Iran in 2022 is the epitome of what Professor Shahram Khosravi is highlighting. The most oppressed minorities from Kurds, to Baloch or Azeri or members of the LGBTQIA communities, and environmentalists, and woman’s rights. Everybody collectively went to the streets and demanded the same thing: equality, justice, love, and hope. It didn’t matter if people were in Iran or Shiraz, and it didn’t matter what their identity was. They were united by this universal, collective humanity and love.

And the young women in Rojava aspire toward the same goal and see the same thing as Professor Shahram mentioned and the revolution: there was a bunch of young women leading the fight against ISIS and leading a new discussion, and conversation about new ways of co-existing together, and beyond the old patriarchal nationalist discussions, and the languages of borders, and colonialism, and oppression, and instead a move towards an alternative awareness, and one towards humanity, and ecology, and environmentalism, and towards gender empowerment, and where the most silenced in our communities are brought to the forefront and given a voice and chair. We see in this new imagined Utopian society, the men taking a back seat, and the patriarchal violence taking a back seat, and colonialism being erased to the background. Borders being removed from the discussions. To me, this is the practice that Professor Shahram eloquently highlighted, and Rushdi’s beautiful exhibition has really brought to the forefront.

Omar Kholeif: Thank you so much. I wanted to take some questions from the audience, and offer the chance for comments. One here for Rushdi and thanking everyone for their presentation. This individual is saying they are moved by all that you said and wanted to know about the I suppose, the difficulty of moving away from darkness, and they ask, Do you still at times feel hatred? About the experiences of your lived experiences, can that hatred be used to fuel your art and thinking in a positive way and curious how you feel about answering that one?

Rushdi Anwar: Yes. So that’s a good question. There’s a simple answer. We cannot fix a problem by making another mistake. Or another problem. So we have to come to the conclusion that the experiences we talked about personally, and also those experiences, are being shared by all members of the panel, as are the difficulties in the region. So, I don’t think it’s going to be solved by repeating it. So if for me, I moved away from darkness, and art and culture give me hope and poetry, and as Professor Shahram mentioned and we came from all of the members of the panels, we come from that region, poetry, and literature is so rich in that area.

That’s one of the things that I remember during the conflict, war, and very difficult times. We always share jokes with each other; that’s how we survive. We always share poetry and songs. We are singing and dancing, and still sometimes, when the bombs are dropping, we are dancing and sharing laughter. So there’s a human way to move away from the darkness. Living in darkness doesn’t help anyone. Doesn’t help me or my community. We have to look for it. If I was living in darkness today, we are not here to discuss about my art practice, in Artes Mundi, and they will be nothing there. That’s my answer, and I moved away from this and looking forward to the bright side.

Omar Kholeif: You mentioned there are numerous other arts beyond the art, music, dance, literature, and one of the individuals here has actually asked if we have any references literary, and particularly fiction or otherwise, that are particularly evocative to anyone in the room that are related to anyone in the room that are related to Rushdi’s practice or the discussion today. Of course, if we need time then we can always post this online later, but if there’s anything immediate that anyone wanted to mention in terms of a text?

Rushdi Anwar: Good question. In the same exhibition, and there’s the poetry by the Kurdish poet Sherko Bekas, and accommodated with the work around the aftermath of the Halabja bombardment. The title of the book, we can post it later on, it’s called “BetterFly Valley”. It’s a beautiful novel and book of poetry written by Kurdish poet and its a small book about 50-80 pages. That’s one of the references for poetry. I’m sure if they knew of anything, or if you think of anything, and recommend?”

Hawzhin Azeez: I tagged my response in the chat. And it’s a text by Michael Gunter, and a wonderful text for those who would like to become more familiar with the history of Kurds and the kinds of oppression in the region since the Sykes-Picot region was established. Anything that Professor Shahram has produced.”

Omar Kholeif: Another question here from someone who thanks us for the conversation, and asking us about how we consider ways of extending art beyond the traditional spaces of art, so how is it that we, we have had the dialogue here, and it’s very much a conversation that is had amongst, and I mean I could probably answer this question already, and this dialogue is actually not through traditional art, and none of us are conventional art people, I would say by any stretch. I suppose, the question is how do we move art and the radical hope art can produce, and spaces that only speak to the art audience, do we have any ideas about how we could do that to move contemporary art beyond to new publics? My answer is conversation is a great way. I don’t think that any of us are from where their recommendations bring people from different disciplinary social, cultural backgrounds into the same room virtually, or physically. That alone can be a beginning for a whole movement or a birth of hope. But, I don’t know if there’s anything else you would like to add?

Hawzhin Azeez: Solidarity. The term solidarity, and that’s what we should be adding to the discussions, and with fellow groups, and connecting community, and mutual aid, and becoming aware of the situation and plight of minorities who are being oppressed. Many people as Rushdi’s exhibition is demonstrating and attempting to resolve really, are not even aware of who the Kurds are, and many other groups who are deeply oppressed, and who the general society, and community, and international community, and the majority as Dr. Omar mentioned aren’t aware they exist. I think when the majority is not aware that a particular oppressed community exist, they do not exist.

Solidarity is very, very powerful. Again, connecting back to gender, we saw with the Kurdish women’s uprisings in Iran and in Rojava that they were dancing in the face of the most challenging situations and still choosing life and I think dance is very, very important. And so beautiful, and powerful, and empowering, and to bring the private into the public sphere, and to open the discussions, and to bring issues and ideas, and we often don’t have a chance to express, and come together in a communal space like a street and community or Town Hall, and the park and have the beautiful discussions, and connect and get to know one another.

Shahram Khosravi: Thank you for these words, beautiful. Going back to dance. You know, it brings bodies, and bodies are important yes? To be in the public spaces and to occupy them. Also artistically, and when I say poetic thinking, and I am not thinking about poetry, and you know and to be romantic, and it’s to participate in the world. To participate in life. I want to recommend a book by Roman Kelly, an American black writer. He is wonderful. “Freedom Dreams” is the title of the book. He writes about surrealism and it was not only an art movement, and according to Roman Kelly surrealism has always been a political movement. The political movement to create a different imagination, and for fostering a kind of imagined life, and imagine the world otherwise. So I think going back to artistic imagination, and poetic thinking, and bringing bodies in the middle of the political scene, and the battle you know. It’s important.

Omar Kholeif: I just wanted to say that we are short of time now. But I wanted to share just some positive and healing feedback from an artist who said they loved the conversation today and she thought the conversation and someone who has experienced inner trauma through art finds a common language through images and not through words, and that has become hugely powerful for her. Again I think the idea of an image culture is important to remember and trauma can be caused by our birth and by political control, and also deeply personal experiences that occur to us, and without us realizing and may be things that are accidental. This individual was a clinical psychologist would became an artist, Joyce Davies, and language for her has been a healing and creating the visual language has been a healing space for her. That’s an important thing to me, and we are all in the process of constructing our own individualized healing languages, or forms of expression separate to each other as well.

We take in these conversations, something that we carry on outside as well, and you know, and it’s a spark of inspiration, and it’s just a desire to write an e-mail of thanks, and you think about all day, these things are important sparks, you know. And one of the things that when I was reflecting on today, I think what’s so particularly special about Rushdi Anwar’s work, and it creates a lyrical space, and a space of although the image before us may not necessarily at first invoke poetry, and song, but look, and move and weave and you find yourself dancing and reflecting, grieving, or wishing and hoping to dream otherwise. I think that movement towards the otherwise and in collective thinking across all of our disciplinary fields has become so important and it’s the possibility for rupture, and the opening is a gift that artists give us, and one that Rushdi I believe not only with this incredible exhibition that you have created for Artes Mundi, and more generally throughout your practice has enabled a lot of us space to feel these things. So for me, and thank you, and to everyone else also. We have a few more moments now I’m told. Each one of us can give their closing thoughts as.

Rushdi Anwar: Thank you. before I start closing, so thank you for all of you being here and the audience, and for Artes Mundi to create this platform for this discussion. And to unpack those issues we talked about. For me, I hope, my art practice we are putting something out there for creating a debate, and dialogue regarding these difficult issues. How we can come closer to each other, and what we share in common rather than what divides us, to look at those aspects, we share in common, and co-existing rather than division and segregation, and moving from each other, and hate us. So I hope my art is doing that. Dr Professor, please?

Hawzhin Azeez: I wanted to reiterate the beautiful gift that Rushdi has given us in his exhibition, and commend what he has done in what I am certain has been a profound effort on his part emotionally, and psychologically to present us with not only his identity, and a piece of his heart and soul to us. So I thank you for that. The other thing I want to thank him for is thank you for occupying as Professor Shahram said, and thank you for occupying a space at the British Museum of Wales, and as a Kurd and whose very identity has been looted. It’s so powerful to have you occupy that space in a British Museum of Wales. Thank you for that. Thank you for Artes Mundi, and Professor Shahram, and Dr Omar as well.

Shahram Khosravi: Thank you to everyone. It was beautiful. I think exactly what we need you know, in the dark days when there’s no hope, and this kind of gathering and just finding each other, and getting engaging in such beautiful conversation about hope, and it is not only you know, it’s important but it’s necessary you know. It’s necessary for life, and it’s not only about democracy, or you know, this or that but for life itself. So, thank you for defending life. Thank you. Thank you very much. Nigel: If I may, and reenter a summation of the conversation which I think very clearly could and should, and will continue. This is just the beginning I think. Specifically around the themes and issues, and not only present in Rushdi’s work, but, one thing that I think through this conversation, we all who have listened, and enjoyed what we have shared with us today.

The importance of how aware we are, and how keenly we feel the interconnectedness, interconnectedness of us all in the global condition that we find ourselves, and how through the important sharing of information, through conversation for that to be generative, and to seek out the light, and seek out the hope in what indeed are dark times especially presently in many areas, but, obviously, very much so in Gaza. Thank you all for listening in wherever you might be, in time, place, geography, space, for the audience from their home, from their work, from being on a bus, or wherever you may be, thank you for tuning in to this At The Table talk, presented in partnership with the British Council. Thank you to the panelists for their eloquence, and their challenge to us, I think, as global citizens. And the prompts that they have signaled and so Omar, Hawzhin Azeez and Shahram, thank you sincerely, and of course, to our good friend Rushdi!

Thank you for not only the conversation today but for work that we have on show presently at the National Museum in Cardiff. The Artes Mundi is always one of our core missions is to establish spaces and to hopefully create platforms for dialogue, and debate that enable us through that exchange and that conversation to learn about ourselves with and through others, and to become more familiar with those cultures and those ideas, and those peoples who we have some familiarity with. But especially those that are new to us in some way or that we have gaps in our knowledge and experience. So today’s talk I think has been a great example of igniting that spark, that Omar mentioned. Thanks again to all of you at home, and thanks again to the panelists.

Comments are closed.