Ismail Khayat’s Legacy: Grandfather of Kurdish Art

By Shajwan Nariman Fatah

In the annals of art scholarship, readers are consistently introduced to and engage with renowned creations by various artists spanning various historical epochs and artistic movements. Amidst this discourse, the East-West dichotomy comes to the forefront, unveiling a significant disparity wherein the artistic contributions of creators from supposedly less prominent geographic locales remain concealed and underexplored. Consequently, this article endeavors to address the prominence of Kurdish art within this discourse, focusing on the oeuvre of Ismail Khayat, a prominent figure referred to as the “Grandfather of Kurdish Art.”

As Khayat stated in one of the interviews when asked if there was something such as “Kurdish Art,” Khayat answered:

“Yes, there is a Kurdish art, but it is not well known outside of Kurdistan. Of course, we as Kurds, our history is not well known. People often know about the Kurds because of the unfortunate events that have happened to us like the genocide. This is how we have become recognized. But the outside world can be better introduced to the Kurds through Kurdish art and by seeing the products of Kurdish artists. However, this effort needs to be organized. It needs to be well done and needs to have the media and all of the roshnbiran (literati) to work towards this project so that Kurdish art can be seen outside of Kurdistan.” (Khayat & Abdullah, 2018, p.55)

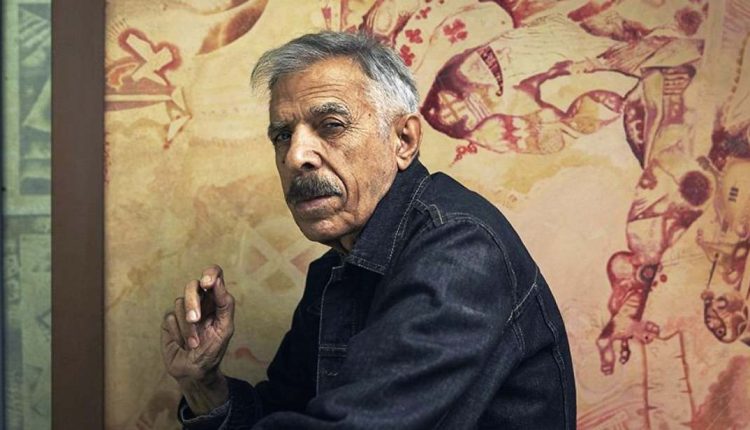

Ismail Khayat (1944 – 2022) emerged as a paramount emblem of plastic arts not only within Iraq at large, but with special significance within the realm of Kurdistan. The concept of ‘plastic art’, originates from the term ‘plasticize’ or to ‘mold’, and essentially entails describing “any art form that involves the activity of modelling or molding into three dimensions. The most common example of plastic art is sculpture itself.” Khayat’s influence permeated the Iraqi artistic panorama and held an even more prominent stature within Kurdistan’s artistic landscape. He is aptly characterized as the mastermind behind the modern visual language within the realm of Kurdish plastic art. Initially, his artistic voyage adhered to the norms of the prevailing discourse within plastic art, echoing the trajectory followed by many artists of his generation. However, he soon embarked on a quest for alternatives, an exploration that was nurtured by the fertile Kurdish surroundings and subsequently led to his artistic evolution. Having joined the Society of Iraqi Plastic Arts in 1965, Khayat later graduated from the Teachers College at Baquba in 1966. In 1992, he assumed the role of art director at the Ministry of Culture in the Kurdistan Region.

Notably, Khayat achieved the distinction of being the creator of the world’s largest painting, an accomplishment that merited his inclusion in the “Guinness Book of Records.” This monumental work portrayed the expanse of the Kurdistan Mountain range extending from Koya Snjaq to Dukan in the Kani Watman regions. It is also essential to state that he is recognized as a trailblazer in contemporary Kurdish art, as he forged a unique artistic approach inspired by Kurdish folklore, symbolism, and Iraqi landscapes, and imbued them with the struggles and isolation experienced by the Kurdish community.

Utilizing a range of artistic mediums, Khayat crafted a portfolio of nearly 8,000 pieces throughout his lifetime. More than 100 of these artworks are currently showcased as part of the Sharjah Art Museum’s Lasting Impressions series, which highlights pivotal figures in the evolution of contemporary Arab art. While his primary medium was painting, Khayat notably veered into sculptural expression during the Kurdish partisan War in the 1990s. He crafted a significant series of boulders adorned with peace messages in the Pirar region of Kurdistan, alongside thousands of smaller painted rocks.

Beyond conventional symbols like the “Evil Eye and the Hamsa,” a hand-shaped emblem with an eye, Khayat frequently employed birds as metaphors for freedom and the fragility of existence. In a poignant series depicting the persecution endured by Kurds, he portrayed ethereal birds drifting away from lifeless bodies. Throughout his professional journey, Khayat presented his creations in numerous exhibitions spanning Iraq, the broader region, and the international stage. His artwork graced galleries in countries including France, the United States, Japan, and beyond. Additionally, he took on the role of art director within the Ministry of Culture for the Kurdistan Regional Government. Khayat’s legacy lives on through his wife, the accomplished artist and actress Gaziza Omer, as well as their children, son Hayas and daughter Hasara. They have seamlessly interwoven the family’s artistic and tailoring heritage into a Kurdish fashion brand named Nakhsh. Hayas took on the role of co-curator for the ongoing exhibition at the Sharjah Art Museum alongside Alya Al-Mulla.

Hayas states that Among his father’s highly acclaimed creations, his ‘Masks’ (Figure 2), stand out prominently as a body of work he meticulously crafted over the course of several decades. Hayas sheds light on their significance, explaining, “a substantial portion of my father’s mask series found its inspiration in my mother’s involvement in the theater, particularly following their marriage in 1989.” Besides Hayas’s statement, here I want to highlight on the elements of his artwork, the title – masks – which entail deep philosophical aspects, if we as viewers read them in terms of semiotics; commonly, masks are used to hide the intentions or the emotions. However, Khayat’s work depicts the paradox of this reality; if we pay a closer look at these faces – we plainly can see the facial expression and the details on these masks – this seems to be open to interpretation. Nationally, this also could be a metaphor for the Anfal genocide (1988), the blindfolds have not disguised the ethnic identities of Kurds!

From these perspectives, Khayat holds the distinction of being the author of the most precise record of the massacres that were perpetrated against the entirety of the Iraqi populace, with a particular focus on the Kurds, during the span of over four decades under the rule of the Iraqi Ba’ath party and the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein. For this reason, his artworks stand as genuine historical chronicles that capture different phases of oppression, forced displacement, and suppression. These artworks were showcased in exclusive exhibitions, serving as a visual testimony to the adversities he personally encountered during this somber era.

Cockrell-Abdullah (2022) states that Khayat has been likened to the renowned “Picasso of Kurdistan.” The honorific “Mamosta” (‘teacher’ in Kurdish) is attributed to Ismail Khayat, reflecting his elevated standing within the realm of artistic endeavors. This honorific not only signifies his pedagogical role as an instructor who has profoundly influenced contemporary artists, but also underscores his emblematic stature within the Kurdish cultural milieu. Cockrell-Abdullah also states:

“During my first year of conducting fieldwork in Kurdistan, I had a number of opportunities to engage with artist Ismail Khayat and his wife, Gaziza, an acclaimed actress, writer and director in her own right, on several occasions both at his home studio and out at public art events. During early visits to Kurdistan, when I asked which artists I should be working with for this study, Ismail Khayat’s name was the very first to come up. I first met him at his home studio. A small but open place with honey-colored wooden floors and plenty of sunlight. This great man and I sat on the floor like kids, and he brought out pieces that he had been working on, one-by-one. [ Figure 3]” (2022, p.14).

In terms of culture and Identity, I would like to go further with Khayat’s style – blending elements from Kurdish cultural stories and symbolism, his artwork enciphers notions of collective struggle and political seclusion. Hailing from Xaneqîn, Southern Kurdistan (Khanaqin, north Iraq), Khayat is a source of inspiration for Kurdish intellectuals and artists.

Executed in an unpretentious manner, Khayat’s mixed-media collage titled ‘Those Who Observe Others Will Succumb to Envy’ (Figure 4) explores superstitions linked to the malevolent gaze, drawing from common expressions and symbols of the Middle East and North Africa. Within this piece, Khayat portrays a hamsa, a symbol featuring a right hand with an eye, and challenges viewers with the artwork’s Arabic caption, prompting them to question their ethical judgment and perception. Thus, he works within and without constrained themes and styles – breaking away from the traditions and implementing his words to depict the integration of multiple cultures – once again this seems to be a revolution for a Kurdish artist to show the hidden abilities through surrealist styles in his works.

Throughout Khayat’s works, recurring motifs of birds symbolize both liberty and the delicate nature of existence. By drawing from Kurdish and Iraqi folk narratives, he delves into the gradual socio-political isolation of Iraq’s Kurdish populace. In a series commemorating the infamous Al Anfal campaign led by former President Saddam Hussein in the late 1980s, which involved the use of chemical weapons on Kurdish towns and the destruction of 3,000 villages, Khayat portrays abstract, ghostly birds soaring away from lifeless bodies.

One of Khayat’s more recent artistic endeavors, titled ‘A Flying Bird’ (Figure 5), showcases a circular canvas that he personally fashioned. On this canvas, a bird is meticulously illustrated using watercolor and ink. Intricately intertwined between these elements are countless intricate details, wherein numerous expressive faces are juxtaposed with one another, and tiny scribbles are interwoven throughout. Drenched in a vivid shade of red, this artwork epitomizes Khayat’s later artistic methodology, which harmonized elements of natural imagery, landscapes, and representational portrayals of human figures. A frequent explorer of the landscapes and urban landscapes of Southern Kurdistan, he absorbed inspiration from these experiences and subsequently reconfigured the diverse visuals within his creative imagination. Birds occupy a recurrent role within Khayat’s oeuvre. According to his son, Khayat was profoundly affected by an early-life encounter with several birds that had perished in harrowing circumstances. Yet, on a more profound level, he viewed them as emblems of peace and freedom. Hayas articulates: “My interpretation is that he held the belief that nature and humanity are interconnected and that in death, we return to nature and influence it in novel ways.” In other words, one could say, apart from personal experiences, a bird in a Kurdish painting could be a symbol of liberty, as historically Kurdish artists, poets, and authors have utilized codes to break the fascist’s rules and the chains that have imprisoned them from flying freely.

References

Al Bustani, H. (2022, November 19). Sharjah Art Museum retrospective pays tribute to ‘Picasso of Iraq’ Ismail Khayat. Retrieved from The National News: link

Cockrell-Abdullah, A. (2022). Critical Artwork, Critical Actions, and the Inclusion of Difference. Journal of Intersectionality. link

Ismail Khayat. (n.d.). Retrieved from Barjeel Art Foundation: link

Khayat, I., & Abdullah, M. (2018). Archiving a Life’s Work: An Interview with Ismail Khayat. The Journal of Intersectionality, 2(2), 52-58. link

Mula Zalal, G. (2022, November 2). Bidding farewell to Kurdistan’s master of visual modernity. Retrieved from The Arab Weekly: link

Sharjah Art Museum retrospective pays tribute to ‘Picasso of Iraq’ Ismail Khayat. (2022, December 26). Retrieved from One. Iq News: link

Comments are closed.