Blockading the Truth: UK Criminalizes Journalists who Support Kurds

By Matt Broomfield

A Greek film-maker’s detention at the UK border under a controversial and little-known anti-terror power has raised concerns about both the increasing targeting of Left-wing journalists by UK police and the continued persecution and harassment of activists, volunteers, and community figures in and around the Kurdish political movement. Both groups face distinct but related challenges, while a broader wave of criminalisation of dissent and repression of civil liberties in the UK is being precipitated by the influence of foreign powers. Award-winning journalist and veteran of the fight against ISIS, Alexis Damoulis, tells KCS he believes his own detention was “tailored to the interests of the Turkish embassy.” The USA and France are just two of the other foreign powers to have exerted undue influence over UK security measures, raising concerns about the politicisation of UK policing to benefit foreign powers.

No Right to Silence

Damoulis’ case is interesting since it highlights the intersection between these two spheres of state repression. The independent film-maker and journalist has produced award-winning documentaries both in Ukraine, speaking to anti-authoritarians and anarchist activists fighting against the Russian invasion, and in Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan). During the latter conflict, he also joined hundreds of other international volunteers to participate in the fight against ISIS with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). As Damoulis stresses, as part of the SDF, he was directly partnered on the ground with the USA and an eighty-country international coalition, including the UK itself.

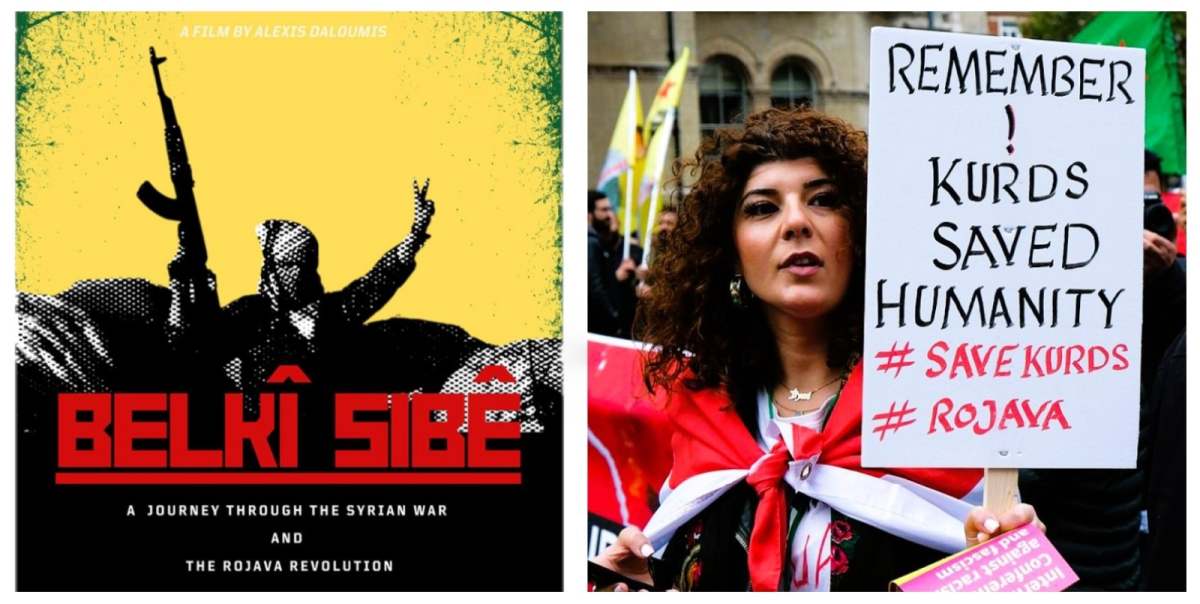

That conflict is the subject of Damoulis’ film Belkî Sibê: A Journey Through the Syrian Civil War And Rojava Revolution. Its Kurdish title, meaning ‘Maybe Tomorrow’, is a knowing wink to the stereotypically less-than-strenuous Middle Eastern relationship to timekeeping and formal organisation, a challenge which many Western volunteers struggled with during months spent waiting for a promised deployment or transfer. In the director’s words:

“This is a volunteer soldier’s film. It unfolds an 18-month journey through war and revolution, during the advance and victory of the Syrian Democratic Forces against ISIS… it depicts military life and battles on the frontlines, as well as civilian life at the rear and the social transformation attempted by the Autonomous Administration.”

Damoulis, a joint UK-Greek citizen, was travelling to the UK in June 2024, travelling “very openly to attend a publicly announced and advertised tour” showing the film in cities around the country. But when he arrived at Luton airport, plain-clothes police operating under pseudonyms (‘Alpha 31’, and so on) were waiting for him. He was then detained under Schedule #7 of the UK’s Terrorism Act (2000).

Officers at the UK’s border can stop anyone they please and ask them questions to determine whether they “appear” to be a person “concerned in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism”. Two aspects of its power make it perhaps Europe’s most powerful and invasive anti-terrorism legislation. First, and uniquely, those detained under Schedule #7 do not have the right to silence. If police do not feel their questions are being answered adequately, the subject can be jailed. And secondly, failure to disclose phone PIN numbers and laptop passwords is also a criminal offence, which can result in a jail sentence.

Damoulis was questioned extensively over his volunteering in Syria, his work, and his documentary film—questions over how and why he made the documentary, who funded it, where he got the footage from, and so forth. After initially refusing to hand over his pin number, he was arrested, and spent the night in police custody, before being released the following day once the police had accessed his devices.

“Being a Journalist is not a Defence”

Notably, in Damoulis’ case, police explicitly acknowledged that they were dealing with journalistic material. Following a high-profile case in which police detained David Miranda, the late partner of journalist Glenn Greenwald, and forced him to hand over electronic devices on the basis of Greenwald’s reporting on sensitive leaks, police practices changed. The investigating officers are now supposed to avoid looking at any “journalistic material,” offering a degree of protection to reporters who worry for their personal safety, as the anonymity and data of their subjects will be compromised if they are forced to disclose sensitive information or give access to their electronic devices.

But as Damoulis says, the investigating officers made clear “being a journalist is not a defence against Schedule #7.” The nominal process through which a journalist should go through their laptop and point out what is and is not journalistic material cannot practically function, since any material is likely to be inextricably mixed up, as in a phone contacts list; there are no guarantees the police will close their eyes to other material; and indeed, any material of interest to the police is de facto likely to be of journalistic interest. “There couldn’t be any process where I point out what is journalistic material and what not,” Damoulis argues.” My devices are full of journalistic material scattered here and there.”

As such, a number of journalists have declined to hand over materials or faced interrogation under the power. I myself was last year detained and questioned by UK police on the basis of my reporting on the Kurdish issue, including in Syrian Kurdistan, prompting the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) to intervene on my behalf. As in Damoulis’ case, police appeared to overstep the nominal remit of the power by interrogating me at length about my reporting, whether I considered my approach objective, how I found my sources, and my own ideological beliefs and stances on Turkish politics and UK policy in the Middle East.

In another high-profile case, French publisher Ernst Moret was stopped and questioned over his role in protests against Emmanuel Macron’s pension reforms in France. Moret also refused to hand over his device passwords and was arrested. Following outcry and a subsequent inquiry, the UK police were reprimanded for the apparent over-reach by the country’s Independent Terrorism Commissioner.

Speaking at a recent event in the UK Parliament to discuss the rising trend in use of Schedule #7, panelists, including Moret’s lawyer Richard Parry, suggested that the power had been used at the behest of the French authorities, leaving the UK police with questions to answer as to why they were doing France’s dirty work for them. The panel event came off the back of another documentary film, Phantom Parrot, which records the travails of human rights activist Muhammad Rabbani. Rabbani, who works to expose rights abuses and torture in the course of the USA’s war on terror, was handed a guilty verdict and a twelve-month suspended sentence for refusing to disclose his own passwords.

When this happens, the subjects of reporting can be exposed, along with personal data and files belonging to the journalist or activist in question. Damoulis says his laptop contained both pictures of his own child, and pictures of other children taken as part of a separate journalistic project. But the journalists and activists are also placed in a dangerous position; if it appears they can no longer protect sources or may be forced to disclose sensitive information to the police, they may lose access or even face threats themselves.

“I Fought Against Terrorists”

Rabbani faced persecution seemingly as a result of his opposition to US policies in the Middle East; Moret, due to his domestic opposition to Emmanuel Macron. And as might be expected, the Kurdish political movement and diaspora in the UK are subjected to particular harassment, persecution and targeting under both direct and indirect pressure from the Turkish authorities.

This persecution takes multiple forms. Volunteers returning from the fight against ISIS, or who travelled to Rojava in a civilian capacity, also face systematic detention and interrogation under Schedule #7. As Damoulis notes, this often results in farcical cases of the UK authorities interrogating individuals who themselves fought with backing from the UK’s Royal Airforce, and even themselves passed information and data on activity by UK ISIS suspects to the UK intelligence agencies. As Damoulis recalls:

“I told them I found it preposterous that I was being interrogated on anti-terrorism grounds, when I was the only person in the room who had fought against actual terrorists!”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a series of cases against UK volunteers in the anti-ISIS fight collapsed or were thrown out of court, though not before causing irrevocable harm to the individuals in question. Dan Burke, a UK volunteer in the fight against ISIS, spent seven months on remand in jail and suffered the humiliation and pain of being labelled ‘Jihadi Dan’ although the UK Armed Forces veteran had in fact risked his life to combat jihadi terrorism. Iida Käyhkö, who researches the criminalization of the Kurdish movement as part of Royal Holloway University’s Information Security Group, asks:

“In whose interest is it that the British state aggressively pursues the allies of Kurdish people under counter-terrorism legislation?”

And these cases, targeting international volunteers, are only the well-publicized tip of the iceberg. For many members of the UK’s Kurdish community, including political representatives as well as ordinary citizens, face detention, harassment and interrogation under Schedule #7 every time they enter or leave the UK. Speaking at the UK parliament event on Schedule #7, the co-chair of the UK’s Democratic Peoples’ Kurdish Assembly Sonia Karimi said: “The Kurdish community come to this country to seek safety, and yet they face threat… Everyone has the right to justice, and to a fair trial. The judicial system has to be functioning.”

People in the Kurdish community are often particularly unaware of their rights and may face the paradoxical situation of being interrogated over their opposition to Turkish government politics, despite the fact that they have been granted asylum in the UK on just that basis. The criminalization of Kurdish political activity and expression has been criticized by experts and community representatives for driving political polarisation around the Kurdish issue and prohibiting the pursuit of a peaceful, negotiated solution. “If the government is genuinely interested in supporting democratic and peaceful development in Kurdistan and the broader Middle East region, its interests are shared by the Kurdish movement,” Käyhkö says.

“Tailored to Turkish Interests”

But why should the UK adopt this seemingly wrong-headed approach, targeting the very Kurdish movement which forms their most trusted partners on the ground in the fight against ISIS? As Damoulis suggests, these interrogations are “tailored to the interests of the Turkish embassy.” The UK’s Kurdish community and activists are low-hanging fruit, which authorities can target to appease Turkey – while also gathering intel which is likely of particular interest to Turkey, given its long-term track record of harassing, imprisoning, and assassinating journalists, activists, and others with links to the Kurdish cause.

Activists have long noted the uncanny series of coincidences through which arrests appear linked to Turkish diplomatic visits to the UK. Dan Burke, the individual mentioned above, was swept up as part of a wrong-headed security operation coming very shortly after Turkey’s autocrat Tayyip Erdogan visited London. A home raid targeting Kurdish residents of London came as then-Prime Minister Theresa May signed a $100 million fighter jet deal in Turkey. At the end of last year, a raid targeting the UK’s Kurdish Community Centre closely followed a high-level meeting in Ankara between UK Defence Minister Grant Shapps and Turkish Defence Minister Yaşar Güler.

Neither detaining journalists and demanding access to their confidential material, nor persecuting and harassing individuals with links to the Kurdish cause, can help the UK keep itself safe. Journalists should be free to report with impunity, and those who fought against ISIS should be granted the respect due veterans of the war against terror, not criminalized themselves. The precise procedure behind any given stop cannot be known, but as Käyhkö notes:

“One of Turkey’s main intelligence priorities is the surveillance and disruption of the Kurdish movement, and Turkey pursues this priority aggressively with its intelligence partners, with the UK as a front-runner.”

Whether intentionally or otherwise, it appears clear the UK is dancing to Turkey’s tune.

Comments are closed.