Babylonian Captivity and Khaybar: The Deadly Narratives in Jewish-Iranian Relations

By Hussain Jummo

The Iranian nation has not been ideologically hostile to Jews since the first civilizational contact in Babylon, when Cyrus entered the city in 539 BC. The name Cyrus was immortalized by the Jews, following the rebuilding of Judaism in Babylon, or the 50-year ordeal of the Babylonian captivity under Nebuchadnezzar.

The Torah states, “Thus says the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I have grasped, to subdue nations before him…”

Jewish-Iranian relations actually begin during the Achaemenid era, with the incorporation of Jews into the Achaemenid Empire. After the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BC and took the Jews into captivity in Babylon, the Jews became a people in exile, known as the Babylonian captivity. In 539 BC, Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and ended the Babylonian empire, and a year later he issued what is known in Jewish sources as the “Decree of Cyrus.”

In the Book of Ezra in the Torah, the text of Cyrus’s decree permitting the Jews to return to Judah and rebuild the Temple is recorded: “Thus says Cyrus king of Persia: The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth and has charged me to build him a house in Jerusalem… Whoever is among you of all his people—may his God be with him—and let him go up to Jerusalem and rebuild the house of the Lord, the God of Israel.” Thanks to this decree, some Jews returned to Jerusalem, while many others chose to remain in Iranian territory, where they settled and integrated into the local communities.

The Achaemenid policy towards religious minorities was characterized by tolerance and respect for their rituals. The kings of Eranshahr allowed the Jews freedom of worship, in contrast to the religious repression practiced by some of their Assyrian and Babylonian predecessors. The Jews’ gratitude for this is reflected in their positive view of Cyrus the Great, who is referred to in the Bible as “the Lord’s Messiah” in the Book of Isaiah because of his role in their liberation. Later Iranian kings, such as Darius I, also contributed to the completion of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 515 BC.

Iran and Babylon occupy a significant place in Jewish religious and historical tradition. Beyond the direct biblical accounts of Cyrus and others, there are later references in Jewish literature praising the relationship between the Persians and the Jews. In the Babylonian Talmud—originally composed in the Iranian-controlled territory of Babylon—there is a symbolic saying that the image of Shushan (Susa), the greatest city of the Achaemenids, should be inscribed on the gates of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The descendants of these Jews were present in these regions when the Andalusian Jewish writer Binyamin al-Tutayli visited Iran in 1167 during his geographically extensive journey. The surviving copy of his book is a summarized version, copied from the lost original, and contains exaggerations regarding numbers, according to historians. Nonetheless, it provides an idea of the conditions and the presence of Jews in major cities far from their original homeland, most of whom were remnants of the Babylonian captivity.

Al-Tutayli mentioned that in Nahawand, there were four thousand Jews living in the “land of atheists,” who obeyed the Shaykh al-Hashishin, as he described. At that time, Nahawand was inhabited by Kurds and was classified among the Kurdish regions by the geographers. These Jews accompanied the Kurds in their conquests and lived among them in the mountains.

Al-Tutayli found large numbers of Jews in good conditions in Ajam and Medea (Iran), including his account of the Jews of Khuzestan near the tomb of the Prophet Daniel. He described how the Jews reside on the prosperous side of the city, while the poor live on the opposite side, separated by a river. According to Al-Tutayli, the poor believe that the secret to the Jews’ wealth lies in the tomb of Daniel. This belief led to a fierce dispute between the two sides, which was resolved by agreeing to move the tomb annually from one side to the other. When the ‘Sultan of Persian Sanggār bin Malakshāh, saw what was happening and how Muslims and Jews were disputing over the tomb, he ordered the construction of a bridge and transported the tomb to that location. A shared place of worship was then established around the tomb of Prophet Daniel, which was suspended by chains over the bridge—a situation that reportedly existed at the time of Al-Tutayli’s account.

Al-Tutayli’s reports on the locations and numbers of Jews are undoubtedly exaggerated, such as his claim that 25,000 Jews live in and around Amadiyah (a region in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq), and that they are dispersed across more than 100 sites in the Khaftian (possibly Haftanin) mountains near the borders of Madi. He states that these Jews are remnants of the first community captured by the Babylonian king Shalmaneser. Ten years before this Jewish traveler’s visit, a prominent Jew named Daoud ibn al-Ruhi had emerged, and Al-Tutayli’s account is rare in mentioning this event.

Daoud ibn al-Ruhi declared rebellion against the ‘King of the Ajam’ (the Seljuk Sultan) and gathered around him the Jews living in the mountains to fight the Christians who controlled Jerusalem, aiming to seize the city and expel them from it. He began spreading his call among the Jews, supporting his claims with false proofs—for example, claiming: “God has raised me to conquer Jerusalem and save you from the yoke of slavery.” A group of simple-minded Jews believed in him and thought he was the awaited Messiah.

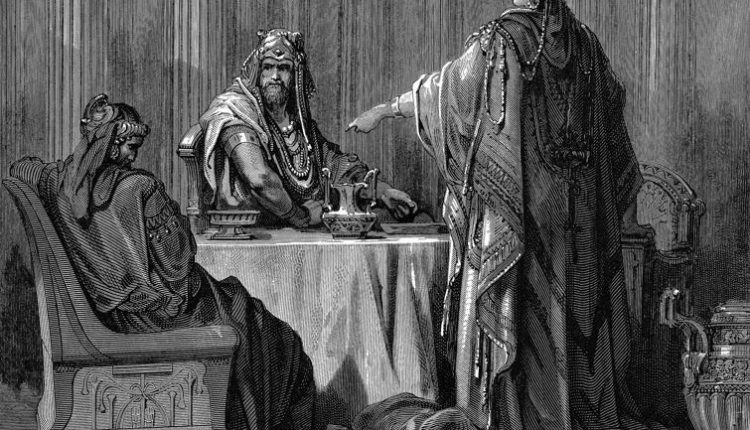

As his influence grew and his words reached the ears of the Sultan of Ajam, he summoned Daoud. The latter appeared before him without fear or hesitation. The Sultan asked him:

“Is it true that you are the king of the Jews?”

Daoud replied: “Yes!”

Immediately, the Sultan ordered Daoud’s arrest and confined him in the great prison of Tabaristan, a city located on the shore of the Qizil Uzun River, to languish there for life. Three days later, the Sultan held a council with his officials to consider the case of the Jews who had disobeyed him. Suddenly, Daoud appeared in the Sultan’s court, free from shackles and chains. Everyone was astonished. The Sultan asked him:

“How did you arrive here, and who released you?”

Daoud responded: “My wisdom and cunning alone. In truth, I am not afraid of you or your ministers.”

The Sultan then ordered his guards to arrest Daoud. However, they could only hear his voice and not see his figure. The Sultan was amazed. He heard Daoud’s voice saying:

“I am now on my way.”

Everyone watched as he departed. The Sultan, his soldiers, and his ministers followed him until they reached the riverbank. They saw Daoud spreading his cloak over the water and crossing to the other side. The Sultan ordered his men to pursue him, and they took boats to cross over. Despite their efforts, they could not find Daoud. It became evident that he was a rare magician, capable of extraordinary feats.

As for Daoud, he muttered some incantations and invoked the Great Name of God, and in just one day he covered the distance that would normally take ten days. He reached Amadiyah and recounted to his followers what had happened to him, causing them to be overwhelmed with awe and amazement at his deeds.

Subsequently, the Sultan of Ajam wrote to the Amir al-Mu’minin, the Caliph of Baghdad, informing him of Daoud’s actions and requesting him to mediate with the Jewish leaders in Baghdad to influence Daoud ibn al-Ruhi through their authority to cease his activities and rebellion. Otherwise, he warned, he would order revenge against all the Jews in his kingdom and exterminate them entirely.

As a result, the Jews in Ajam suffered great hardship. They wrote to their leaders in Baghdad, pleading for salvation and urging them to guide Daoud onto the right path to prevent innocent bloodshed.

Immediately, the Jewish leaders composed a letter to Daoud in which they pointed out his falsehoods and revealed his deception. They concluded their letter with the following words:

“Be informed that the time for the appearance of the Messiah has not yet come, and we have no evidence of his imminent arrival. This matter does not come through violence nor by breaking the vow of obedience. We demand that you desist from your actions, or we will excommunicate you from the congregation of the Children of Israel.”

A copy of this letter was sent to the chief Zakai and Yusuf al-Falakki, known as Burhan al-Falak, in Mosul, to be forwarded to Daoud ibn al-Ruhi. The leaders of Mosul and Burhan al-Falak obeyed the order and sent a message to Daoud, filled with persuasion and threats. However, he did not change his falsehoods or abandon his misguided actions.

When the Amir of the Seljuks, who was a follower of the King of Ajam, came to power, he devised a plot to eliminate Daoud ibn al-Ruhi. He summoned his father-in-law and offered him ten thousand dinars if he killed his son-in-law. The man entered Daoud’s house while he was sleeping in his bed and murdered him. Thus, his life was ended, and the Jews were freed from his evil influence.

However, the King of Ajam still harbored resentment against the Jews residing in his kingdom. They wrote to Ras al-Jalut, seeking his intercession with the king of Ajam due to his favor and high status. The leader of the Jews sent an appeal to the king, offering a large sum of one hundred thousand gold dinars. In response, the king issued a pardon, and the region was relieved from turmoil.

Al-Tutayli continues after the story of Daoud ibn al-Ruhi: From Mount Amadiyah, a traveler journeys ten days eastward to Hamadan, known in ancient times as Madi, the great city mentioned in the Torah, which is home to about fifty thousand Jews. In its church are the tombs of Mordecai and Esther. Who are they?

The story of Mordecai and Esther is among the most significant foundational narratives of the Jewish emotional tradition. The scene is set in the court of the Achaemenids, who had liberated the Jews from captivity, and some of the remaining Jews moved to major cities in Eranshahr. Some of them rose to prominent positions, such as Mordecai, who nearly involved his people in a genocide due to his refusal to bow to the Persian king’s minister, Haman. Haman took revenge on all the Jews and persuaded King Ahasuerus (Xerxes) to issue a decree to kill them en masse for insulting the kingdom.

Mordecai, a devout Jew, argued that he worshipped only God. He took responsibility for his faith and for all the Jews whom the Minister sought to lead to death. Meanwhile, Mordecai faced two options: either to retreat, seek forgiveness publicly, bow, and worship the minister of the Achaemenid Empire, or to attempt to save his people by other means. He had a cousin whom he raised as his own daughter. When Ahasuerus killed his wife, the queen, he asked Mordecai to bring virgins for him to choose a new wife. Among them was his cousin Esther, a name in Persian meaning “star.”

Ahasuerus chose Esther as his wife with great regard, unaware that she was Jewish.

Mordecai turned to Esther to save her people from extermination, which required her to reveal her true identity. Esther had no choice but to risk her life and plead with her king and husband to save her people; otherwise, the genocidal decree would not spare her from execution. Since the king could not revoke his decree, he devised a solution to oppose it. He issued a law for the first time in the history of the Achaemenid Empire to legalize self-defense—even against authority itself. The Jews took up arms and defended themselves in order to survive the near-total annihilation of their people.

The day on which this royal decree was issued is known as Purim, and it is celebrated by Jews every year on March 13. They perform various rituals, including special prayers, supplications, and fasting. The story behind this holiday is the main reason for the fame of the shrine of Mordecai and Esther in Hamadan, the ancient capital of Media.

Jewish life in Iran was not always idyllic and comfortable; it experienced periods of persecution during the Sassanid era due to the strict Zoroastrian influence. However, the Jewish population was notably large in major cities such as Isfahan, which was known as a Jewish city. One of its leaders led a serious rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate. Nevertheless, these disturbances were sporadic, and the Jews enjoyed long periods of peace. Most importantly, their conflicts were with the authorities, and there are no recorded incidents of mass killings by local populations against them. This can be attributed to the concept of authority at that time, which was effectively separate from the people, not representing them directly. Instead, authority was a synthesis that ruled in the name of God and religious laws.

In any case, there is a specific date marking the end of the Jewish narrative that extends from Cyrus the Great in the sixth century BCE—namely, the day when Shah Ismail Safavi declared Twelver as the official state religion.

Scholars from Jabal Amil and Arab scholars who arrived to establish the ‘State of Faith’ in the Shah’s land had to present Shiite hadiths and narratives centered around the awaited Mahdi, who, according to these traditions, would meet with Jesus (Isa ibn Maryam) in Jerusalem, where he would pray behind him. When the Shiite doctrine was reconstructed through scholars such as Sheikh Ali al-Karaki and Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi, numerous stories about the ‘impurity of the Jews’ were incorporated. Public sermons began to openly curse the Jews and portray them as exemplars of negative traits.

This marked the beginning of the deterioration of Iranian-Jewish relations, lasting until the end of the Qajar dynasty in 1925. Relations between Jews and Iranians were then restored throughout the reign of the Shah, continuing until the year of his overthrow by Khomeini in 1979.

Generally, the Safavid era was a dark period for Iranian Jews, characterized by severe persecution. Their numbers declined due to killings, forced displacement, and coerced conversions to Islam during the reign of Shah Abbas the Great. Their living conditions worsened, with most of them confined to isolated ghettos within major cities. This situation persisted until the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1736, when Nader Shah Afshar came to power.

Despite these hardships, Jews devised ways to endure; they imagined inspiring stories—perhaps influenced by the myth of Esther and Mordecai as symbols of impending salvation—and patiently awaited relief. The legacy of that era continues to be remembered in Iranian Jewish memory through proverbs and stories that depict the Safavid Shah as another Pharaoh who tested their faith.

When Islamists ruled Iran, their treatment of Jews was more courteous than what was documented during the Safavid and Qajar eras. This was not due to a fundamental shift in Shiite doctrine but rather because the distinction became useful once there was a state called Israel. As a result, the remaining Jews in Iran often received preferential treatment during the era of the Islamic Revolution.

However, the wave of radical hostility towards Israel within the ideology of the Islamic Republic has become a long-term dilemma. The Mahdavi doctrine no longer merely envisions the Mahdi praying in Jerusalem with Jesus behind him; now, the entire city has become associated with Jews—a new situation for Shiite jurisprudence compared to the Safavid and Qajar periods. An essential part of the heroic image in Shiite heritage, attributed to Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, is linked to the conquest of the Jewish fortress of Khaybar. There seems to be little willingness to focus on the Imam’s heroism outside the “Khaybar culture,” despite the numerous stories from influential fundamentalists that highlight such narratives in popular culture.

Today, as Iran—both the state and society—lives under an existential threat amid the Israeli conflict, it appears too late for the self-reform that should have begun before or immediately after October 7, 2023.

Above all, there are no Iranian Mordechais or Estheres in Israel to save Tehran. Most likely, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has concluded that this country is merely an extension of the Babylonian captivity culture. Between these two deadly narratives, it is certain that there is no Cyrus figure on the horizon for the region.

Comments are closed.